How to spot fake no claim discount letters

Fake no claim discount (NCD) letters are popping up all over the auto insurance onboarding and insurer-switching workflows. Just look at this Irishman who (almost) got away with no claims discount fraud twice in one month.

In 2026, this is quietly becoming a costly problem for insurers and intermediaries who rely on claims history to price risk accurately.

Fake or forged NCD letters can lead to underpriced premiums, distorted risk models, and downstream insurance fraud.

NCD letters are increasingly shared as PDFs or scans, often generated through customer portals or email rather than mailed originals. This makes them prime for modern fraud tactics like document fraud templates and AI automated fakes.

When NCD letter fraud and NCD letter scams happen during policy switching, cross-border moves, and fleet insurance onboarding, insurance agencies need to be prepared to spot fraud before it has a lasting impact on the business.

Read on to learn what NCD letters are, how they’re being forged, how to spot a fake, and how AI-powered tools can help.

Check out our “how to spot fake documents” blog to learn about more common document forgeries.

What is a NCD letter?

A no claim discount (NCD) letter is an insurance document used to evidence a policyholder’s claims history over a defined period. Insurance companies issue it upon request to prove whether a driver, business, or fleet has remained claim-free.

While NCD letter is the most common term, these documents have different names depending on where the insurer is based:

- No claims discount (UK, Ireland).

- No claims bonus (UK, APAC, India).

- Claims history/experience letter (North America).

- Bonus-malus certificate/statement (Europe).

At a glance, NCD letters usually look like ordinary correspondence from an insurance company. They’re usually short formal letters or statement-style PDFs, written on insurer or broker letterhead, and addressed directly to the policyholder. In most cases, they resemble routine policy communications rather than technical insurance records, which is why they’re often trusted at face value.

However, that surface familiarity is misleading. Depending on how and where the letter is generated, an NCD letter may be a one-page branded PDF, a longer policy statement excerpt, or a minimal portal export with no signature at all. Some are signed by underwriters or brokers, others are automatically generated without human sign-off.

Letterheads, disclaimers, formatting density, and even the level of detail included can vary dramatically between insurers, countries, and distribution channels.

There is no regulator-mandated format, no universal issuer, and no central registry. Their appearance, structure, terminology, and delivery method vary significantly depending on the insurer, country, and distribution channel.

In practice, genuine NCD letters can differ across several dimensions:

- Issuer type. Some are issued directly by insurers, others by brokers or intermediaries, and many are autogenerated through customer portals rather than manually signed documents.

- Regional terminology. The same concept may be described as a no claims discount, no claims bonus, claims history letter, or bonus-malus statement, depending on jurisdiction.

- Format and layout. Documents range from branded letterheads to plain-text PDFs, portal exports, or embedded sections within broader policy documents.

- Calculation logic. Some insurers state claim-free years explicitly, while others reference discount percentages or bonus classes that require contextual interpretation.

- Delivery method. Most are shared digitally as PDFs, scans, or downloads, with physical originals now relatively uncommon.

Despite this variability, genuine NCD letters usually contain a consistent set of functional elements:

- Policyholder identification. The insured individual or entity tied to the claims history.

- Policy reference. A policy number or internal identifier used by the issuer.

- Coverage period. The timeframe over which claims activity was assessed.

- Claims statement. A declaration confirming no claims or summarizing claims made.

- Discount or bonus outcome. The resulting claim-free duration or classification.

- Issuer attribution. Clear identification of the insurer or broker responsible for the statement.

- Issue context. An issuance date and, often, disclaimers about transferability or validity.

This lack of standardization is precisely what makes NCD letters difficult to verify manually.

Reviewers cannot rely on fixed templates or visual familiarity alone. Document fraud detection must focus on structural consistency, internal logic, and document construction, rather than surface appearance or issuer branding.

Together, these characteristics make NCD letters a high-risk but high-impact document in insurance fraud detection, trusted for pricing decisions yet inherently vulnerable to manipulation due to their flexible formats.

An example of an NCD letter for illustrative purposes only.

Why NCD letters are important

NCD letters play a direct role in how insurers price risk. They influence premiums, eligibility, and underwriting decisions, often acting as the deciding factor between a standard rate and a heavily discounted policy. After several years of no claims, you could be looking at as much as a 60% lower premium, making no-claims discount fraud one of the fastest growing schemes in the auto insurance industry.

Here’s how NCD letters are used for document verification across insurance and adjacent workflows:

- Motor insurance underwriting. Insurers rely on NCD letters to transfer claim-free history when a policyholder switches providers, directly affecting premium calculations and acceptance decisions.

- Cross-border insurance transfers. When individuals relocate, NCD letters are often the only portable evidence of prior driving or claims history, making them critical and difficult to independently verify.

- Fleet and commercial insurance. Businesses use aggregated claims history letters to negotiate pricing for multi-vehicle or multi-driver policies, where small distortions scale into large losses.

- Broker-led policy placement. Brokers submit NCD letters on behalf of customers to secure better terms, placing trust in documents they did not issue themselves.

NCD letters are frequently treated as trustworthy documents because they come from insurers and reference historical policy data. However, their private, non-standardized nature means there is massive margin for fraudulent behaviour. All a fraud ring needs is one insurer’s letterhead to send out fakes en masse.

That combination of high financial impact and high variability is exactly why fake NCD letters are attractive in insurance fraud and why missing one can quietly erode underwriting margins.

If you’d like to know how fraudsters are creating all these fake NCD letters, check out our “Types of fraud” blog to learn more about their tactics.

Threat intel: Template data about fake NCD letters

Our Threat Intelligence Unit collects data about template farms which make and distribute fake document templates for fraudulent purposes.

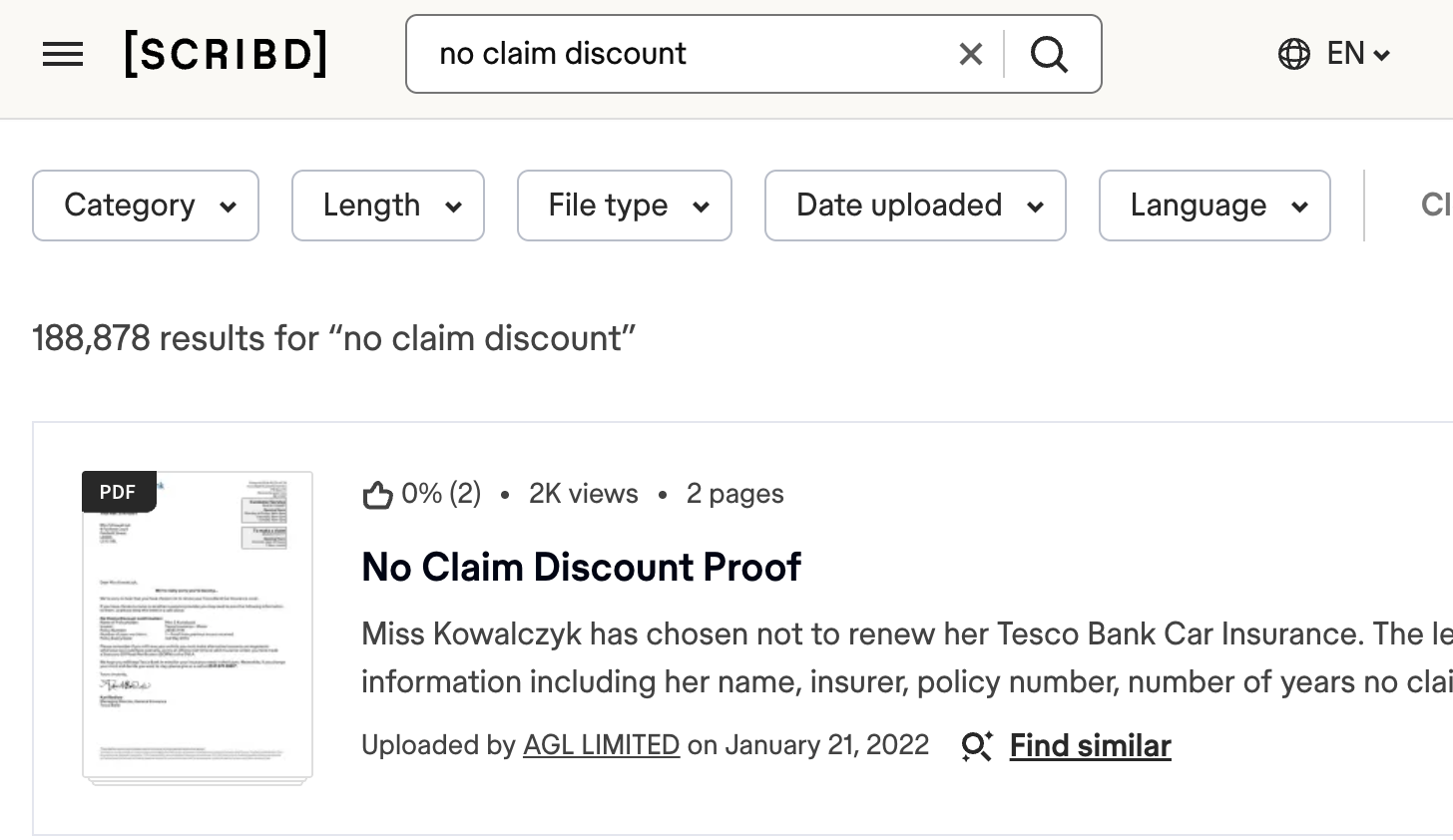

During our research we haven't yet cataloged many no claim documents, however, they are still very prevalent online. A simple search on Scribd.com (a well known template hub) reveals over 188,000+ results for this document, revealing a high demand for online templates.

Search results for "no claim discount" on Scribd.

Threat level: Legitimate no claim discount letters would come from an official insurer. There is no legitimate reason for an individual to need access to these documents online.

Any NCD letter derived from an online template should be treated as high risk.

5 Signs of a forged or fake NCD letter

As we already stated, spotting fake NCD letters is uniquely difficult because there is no single legitimate format to compare against. Issuers and layouts vary widely by region. Instead of surface level checks, modern NCD letter fraud requires AI-powered verification that can assess structure and consistency without relying on fixed templates.

That being said, there are some universal signs that span issuers, regions, and formats.

The red flags below focus only on those universal signals: required document elements, internal logic, and file construction.

These checks can surface obvious fraud manually, but at scale AI document verification is still necessary.

1. Inconsistent formatting

Even with format variability, genuine NCD letters still present their core fields consistently within the document.

- Claims statement formatting differs from surrounding text. This is the critical information of an NCD, if the no-claims declaration, period, or number of claims on the policy appears resized, misaligned, or visually distinct from adjacent paragraphs it’s a clear indicator of manipulation.

- Claims statement breaks document flow. The no-claims declaration interrupts paragraph spacing or alignment, sitting outside the normal text rhythm of the letter rather than reading as part of a continuous statement.

- Coverage period uses mixed date structures. Start and end dates follow a different format, ordering, or typographic treatment than the issue date, suggesting they were added separately.

- Issuer identity lacks structural anchoring. Insurer or broker details appear without a consistent header or footer structure, or shift position relative to the rest of the content.

- Document structure is partially rasterized. Key verification fields are embedded as images while surrounding text remains selectable, indicating selective reconstruction rather than native generation.

2. Incorrect or misleading information

Fake NCD letters often fail when core fields are checked against each other.

- Guarantees of future pricing. Statements implying that the NCD will “guarantee” a specific premium or rate with another insurer.

- Absolute or unlimited claims language. Phrases such as “no claims ever” or “lifetime claim-free status,” which insurers do not certify.

- Transferability claims without limitation. Language suggesting the NCD is universally valid across all insurers or countries, without conditions or disclaimers.

- Regulatory or government references. Mentions of transport authorities, regulators, or official registries. These entities do not issue or validate NCD letters.

- Claims outcomes beyond scope. Assertions about fault, liability decisions, or legal responsibility rather than a simple record of claims history.

- Missing core elements. One or more required fields (issuer, policy reference, coverage period, claims statement) are absent.

3. Bad math and uncharacteristic figures

While NCD letters are not financial statements, their outcomes must still reconcile logically.

- Claim-free duration exceeds the maximum possible period. The letter states more claim-free years than the policy could have existed based on typical policy lifecycles.

- Arithmetic language applied to claims history. Use of calculations, formulas, or cumulative totals (for example, “claims avoided” or “claims saved”) rather than simple declarative statements.

- Conflicting outcomes. Different sections of the letter state different claim-free durations or discount results.

4. NCD letter inconsistencies

Internal contradictions are one of the strongest indicators of forgery.

- Unexplained mixing of claims history systems. The letter presents claim-free history using both year-based descriptions and bonus-malus class references without explaining the relationship between them, even though legitimate insurers typically anchor the document to a single system or clearly describe any conversion.

- Policy reference not used consistently. A policy number is listed but not referenced in the claims statement or coverage description, or two different numbers are referenced without explanation.

- Claim-free duration exceeds coverage period. The stated number of claim-free years cannot be supported by the policy dates shown.

- Issue date and claims scope mismatch. The letter is issued during an active policy period but presents the claims history as complete or final without clarifying that it reflects only a partial or interim period.

5. Metadata discrepancies

How the file was created often reveals more than how it looks.

- Consumer editing software in metadata. The file shows creation or modification in general-purpose design or PDF editing tools.

- Screenshots. These documents are typically issued as PDFs. Physical photos or screenshots of documents means extra effort to change format that can indicate risk.

- Individual authorship markers. Metadata lists a personal name or device instead of an organizational system or insurance agency.

- Mixed text and image fields. The main body of the letter is selectable text, but key fields such as the claim-free statement, policy number, or coverage dates appear as images or screenshots, which is consistent with selective editing of an otherwise legitimate document.

Disclaimer: These red flags can help catch obvious fake NCD letters, but they’re not enough on their own. Fraudsters can change formatting and edit only a few high-impact fields (like the coverage period or claim-free duration) while keeping everything else looking normal. Verifying these documents reliably at scale requires AI-powered detection that can assess document structure and file integrity, not just what the letter appears to say.

How to verify a NCD letter

NCD letters verified during insurance underwriting, broker-led policy placement, and cross-border policy transfers can be done manually or through automation, but manual checks are increasingly unreliable.

NCD letters are easy to alter with basic editing tools, lack standardized formats, and are often submitted as standalone PDFs with no external reference point. Even experienced reviewers struggle to assess authenticity consistently, especially when volumes increase or documents originate from unfamiliar insurers or countries.

AI-powered automation offers a more reliable alternative. Instead of relying on issuer familiarity or fixed templates, AI can evaluate how the document was constructed, whether its internal fields behave consistently, and whether it matches known patterns of legitimate insurer-issued files.

That said, many organizations still rely on manual verification. If you’re verifying NCD letters by hand, the following checks can help reduce risk.

Manual verification of NCD letters

The best way to verify NCD letters manually is to check for the red flags we mentioned above. Once you’ve exhausted those, you can attempt to verify them externally using the following sources:

- Contact the insurer. Reach out to the agency that issued the letter to ensure it reflects accurate data.

- Check active or historical coverage via national insurance databases. In some markets, public or industry-run registries can confirm whether a vehicle was insured during the period claimed. For example, in the UK the Motor Insurance Database (MID) can be used to confirm whether a vehicle was insured at specific points in time, which helps validate whether a claimed coverage window is even possible.

- Validate issuer legitimacy independently. Confirm that the named insurer or broker is a regulated entity in the stated jurisdiction using official regulatory registers, rather than relying on branding or logos alone. For example, across the EU, insurer authorisation can be checked via national regulators coordinated through the European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority (EIOPA), which maintains guidance and links to official registers.

Keep in mind: These checks can help identify obvious issues, but they don’t scale. As NCD letter fraud becomes more targeted and subtle, manual verification alone cannot keep pace with the volume or sophistication of modern document forgery.

Using AI and machine learning to spot fake NCD letters

Because NCD letters have no fixed format, template-based checks and visual review break down quickly. AI-powered verification is effective precisely because it does not rely on knowing what a “correct” NCD letter should look like.

Instead, it evaluates whether the document behaves like something legitimately produced by an insurer or broker.

Key benefits of using AI to detect fake NCD letters include:

- Structural consistency analysis. AI evaluates how the document was built, checking whether core fields like coverage period, claims statement, and issuer details behave as part of a single, coherent file rather than selectively edited elements.

- Issuer-agnostic detection. The system does not depend on insurer-specific templates or regional formats, making it effective across markets and unfamiliar issuers.

- Reduced false positives at scale. By focusing on structure rather than content, AI avoids penalizing legitimate format variation while still flagging high-risk documents.

Automation vs. AI

Automation relies on rules. For NCD letters, that might include checks like “a policy number is present” or “a coverage period is filled in.” These controls catch missing information, but they cannot adapt to emerging tactics.

AI goes further by learning how genuine insurer-issued documents are constructed and how fraudulent ones tend to break under scrutiny. It adapts as fraud techniques evolve, detects subtle inconsistencies, and connects patterns across multiple submissions. AI is far better suited to NCD letter verification.

Conclusion

Fake NCD letters distort risk assessment and pricing, allowing policyholders to secure discounts they haven’t earned, quietly shifting costs onto insurers and honest customers.

Because NCD letters are private, non-standardized documents, manual checks struggle to keep up. Visual inspection and issuer familiarity are no longer reliable defenses against targeted edits, reused documents, or reconstructed PDFs.

Resistant Documents addresses this by focusing on structural analysis rather than reading document contents. By evaluating how an NCD letter was built, not how it looks, Resistant AI can detect subtle manipulation, reused patterns, and file-level anomalies that human reviewers and rules-based systems miss.

As NCD letter fraud continues to scale across insurers, brokers, and borders, AI-powered document verification is the only approach that can deliver consistent, defensible decisions at speed.

Scroll down to book a demo.

Frequently asked questions (FAQ)

Hungry for more fake NCD letter content? Here are some of the most frequently asked fake NCD letter questions from around the web.

What is a no claims discount (NCD) letter?

A no claims discount (NCD) letter is a document issued by an insurer or broker confirming how long a policyholder has gone without making an insurance claim. It is typically used when switching insurers to transfer a claim-free history and apply a premium discount.

Can NCD letters be transferred between countries?

Sometimes, but not always. Many insurers accept foreign NCD letters on a discretionary basis, often applying conversion rules or caps. Others reject them entirely due to differences in claims systems, discount calculations, or lack of verification mechanisms.

How to spot fake NCD letters with AI?

Resistant AI can detect fake NCD letters by analyzing document structure, internal consistency, and file construction rather than relying on fixed templates.

What’s the difference between an NCD letter, a claims history letter, and a policy certificate?

NCD letters, claims history letters, and policy certificates all relate to insurance coverage, but vary in how much detail they contain, how formal they are, and what aspects of a policy they describe.

NCD letter: A short, declarative statement about claim-free status.

- Issued by: Insurer or broker.

- Characteristics:

- Usually a brief letter or single-page PDF.

- Focuses on a claim-free declaration rather than listing individual events.

- Often written in plain language rather than tabular form.

- May include disclaimers about transferability or validity.

- Usually a brief letter or single-page PDF.

Claims history letter: A factual record of claims activity.

- Issued by: Insurer.

- Characteristics:

- Typically longer and more detailed than an NCD letter.

- Lists claims explicitly or states their absence over a defined period.

- May include dates, claim references, or claim types.

- Often structured more like a report than a letter.

- Typically longer and more detailed than an NCD letter.

Policy certificate: Formal proof that coverage existed.

- Issued by: Insurer.

- Characteristics:

- Uses standardized insurance terminology and layout.

- Clearly states policy number, coverage dates, and insured parties.

- Often includes regulatory language or compliance statements.

- Does not describe claims activity or claim-free status.

- Uses standardized insurance terminology and layout.

Is there software to detect fake NCD letters?

Yes. Resistant AI detects fake NCD letters using structural analysis rather than content scanning. This allows insurers to verify documents across issuers and regions, identify subtle tampering, and catch fraud that bypasses manual review and rules-based automation.

Who needs to check for fake NCD letters?

Fake NCD letters most often surface during underwriting and policy administration, where individual reviewers are required to assess claims history under time and volume pressure. The roles most exposed include:

- Motor insurance underwriters. Review NCD letters during policy switching to determine whether a claimed claim-free history should influence pricing and acceptance.

- Insurance brokers and account managers. Validate customer-submitted NCD letters before placing or renewing policies with insurers.

- Fleet and commercial underwriting teams. Assess aggregated claims history documents where inflated or fabricated NCD information can materially impact fleet pricing.

- Cross-border underwriting specialists. Evaluate foreign NCD letters where issuer familiarity is low and external verification options are limited.

- Fraud and compliance analysts. Monitor patterns of document reuse, manipulation, or misrepresentation across multiple submissions and customers.

Is making a fake NCD letter illegal?

Yes. Creating or using a fake NCD letter is considered insurance fraud. Penalties can include policy cancellation, denial of claims, financial penalties, and criminal charges, depending on the severity and intent of the fraud.