You might be interested in

"And I probably shouldn’t say this, but when you see one cockroach, there are probably more… Everyone should be forewarned on this.”

Jamie Dimon

CEO JPMorgan Chase

Jamie Dimon

CEO JPMorgan Chase

Jamie Dimon’s recent quote on October 16th, 2025 about cockroaches and a string of high profile trade finance bankruptcies brought a part of finance into focus that is rarely mentioned, considered “niche,” even. But it actually powers the supply chain behind pretty much every single item we buy: supply chain financing in general and factoring in particular.

Factoring (invoice financing) or supply-chain financing in general ties the financing decision to a specific project, delivery, or invoice. Let’s stick to the term “factoring,” where a seller issues an invoice expecting the customer to pay them in 30 to 120 days.

But it would be really convenient to get paid right away. So, the seller (e.g. First Brands in the recent case) waiting to be paid sells the receivable tied to a specific invoice to the factor (e.g. Katsumi Global in the same case) with a small discount. The factor pays the seller immediately and collects the money paid by the customer in 30 to 120 days, according to the invoice payment terms. The discount covers the cost of lending and the risks: customer default, disputes, etc.

In some cases, the seller sends the invoices and other documents to the factor. As the factor’s familiarity with the seller increases, the only thing sent is a list (with customers, amounts, invoice numbers, payment dates, etc.). And, sometimes, only a total.

This arrangement is obviously prone to risks. It can (and often does) go wrong all the time due to commercial disputes, credit risk and last, but not least, fraud. People in the industry often tell me that 5% of the invoices they finance could be, put very politely, “administratively deficient.”

Less politely, this denotes a non-existent, fake, or manipulated invoice that the Seller actually intends to pay back. Possibly using the proceeds of another invoice. As Matt Levine says:

“And then one thing leads to another and maybe you are paying $11.18 million for $2.3 million worth of receipts, oops."

First Brands, an automotive parts company, recently went bankrupt after getting caught for this very issue. Matt Levine described it like this:

“First, in many instances, the amount set forth on a factored invoice did not accurately reflect a customer’s order, without any apparent reason for the discrepancy. For example, in some instances, the amount set forth in a factored invoice was ten or more times higher than the actual amount of an invoice.

Second, in many instances, purported invoices representing customer orders were created and submitted to third-party factoring parties for payment even though the Debtors’ books and records, in some cases, do not reflect that such customer invoices existed.

Third, in many instances the same invoice was factored more than once to different third-party factors.”

There have been numerous attempts to create consortium-style solutions to that last problem (with their usual limitations in uptake, reach, willingness to share information, etc), but the first two reasons can absolutely be addressed.

What you should be doing instead is checking the substance of the business relationship behind each invoice.

The problem with checking the invoice directly is that invoices are naturally created by the company you are funding. And as such are under their full control.

Sure, the processes used to create the "dummy" invoices (as in the First Brands Group case) are often different from the processes used to issue the real invoices. But this is not a hard rule. You can conceivably use the exact same process to create both real and fake invoices. Actually, for any serious criminal, this is what they should be doing (not legal advice, but a smart move nonetheless).

That’s why detecting this type of fraud may require information beyond the invoices themselves. We have seen and confirmed many factoring frauds, but we detected most of them when analyzing the documentation supporting the invoice: the purchase order created by the customer, the bill of lading provided by the logistics company, goods acceptance receipt, and anything else that normally gets stapled to the invoice upon issuance.

All those documents are created by third parties independent of the invoice issuer and have to be modified or forged from scratch by the criminal. So, the process to validate the business cases and invoices already exists. It may not be perfect, but it certainly beats blind trust.

Current practice of effectively financing a list of numbers and amounts in an excel sheet or an API is based on old logic. Reading a stack of invoices with stapled purchase orders and other documents used to be work intensive and something your colleagues don't want to spend their time on. Well, the good news is that the current generation of Al system allows you to turn a stack of invoices and other documents into a risk score in a couple of minutes with no humans involved.

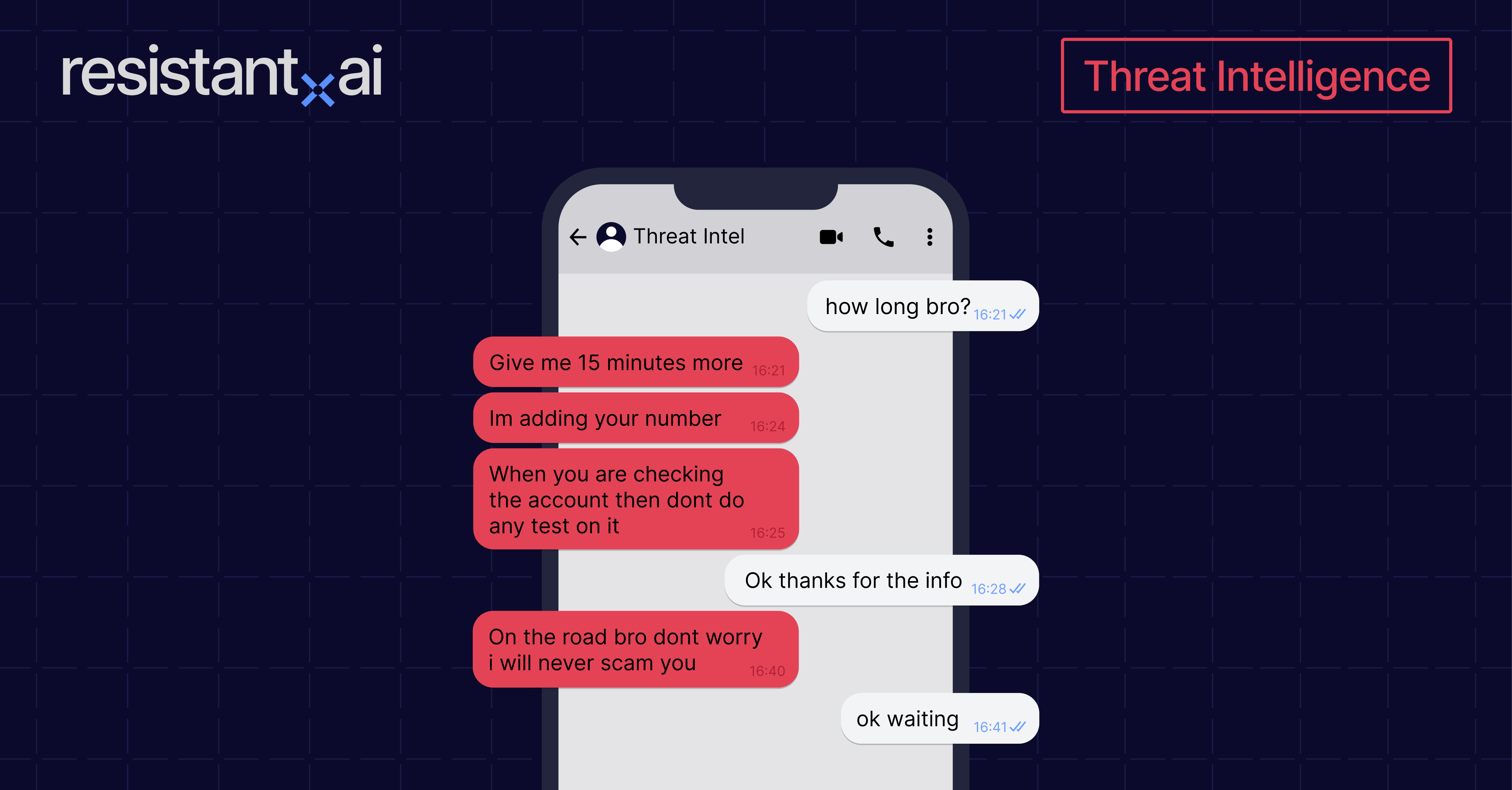

The magic behind the detection concept is that most factoring fraud is repetitive, borderline boring and targets multiple victims. As Matt Levine puts it:

“So, probably in 60 days you will have to do this again, but more so: You’ll have to make even more fake invoices to borrow even more money to pay back the money you borrowed from the previous fake invoices. And this snowballs […] Probably when you first do this, it is a wrenching moral quandary that you keep quiet out of shame and fear. You make the fake invoices late at night when no one else is in the office. You tell only the people who absolutely need to know, and you tell them in person in a nervous whisper in the bathroom with the water running so no one can overhear. You don’t put it in writing. But then you do it again in 60 days. And after you’ve been doing it for a while, everyone will get comfortable, and eventually you’ll just send mass emails like ‘hey everyone, time to fake the invoices again.’”

So, we are not looking for a perfect fraud detection process (this would require some human judgement even at the current level of technology), but we are looking for a process that makes sustained, long-term and repetitive fraud hard to conceal. And that is more sophisticated than a quarterly financial statements audit by the factor.

The high-level process is actually simple:

The use of AI, supervised with a healthy dose of skepticism, allows you to comb through the large volumes of semi-structured data, extract the logic, and validate the key aspects of the operations you are financing. This is exactly the kind of business application where AI can be used effectively, to gain more insight into previously opaque risks.

It is exactly the kind of pressure that makes the cockroaches scarce. Until they learn, adapt and get better, and the eternal cycle restarts. Because, as a company, we can’t accept the old adage that the optimal amount of fraud is non-zero.

Resistant Documents can help you squash your cockroaches. Scroll down to book a demo.