You might be interested in

Authorized push payment (APP) fraud is the largest category of fraud in the United Kingdom, has been subject of congressional hearings in the US, and is the first priority of fraud departments in banks and payment firms worldwide. Lately, the blame for this fraud boom has been directed at neobanks and payments-focused fintechs, which are described as hotbeds for fraudsters and inherently more risky to consumers.

But this is an incomplete and misleading picture, especially as increasing regulatory repercussions raise the stakes of bad reputations: in fact, these relative newcomers to the finance industry are at disproportionately the greatest risk from this kind of fraud for precisely the same reasons that they have made lives easier for their users.

The principle behind APP fraud, also known as P2P or instant payment fraud, is very simple. As the system security of most payments applications has increased, the attention of attackers has shifted from technical hacks to softer targets—humans. Most people are kind, trusting, and believe in the good intentions of others, and this makes them perfect targets for fraudsters. Romance scams, CEO scams, business email compromise, bank security calls, and countless other subcategories of scams have one thing in common: a legitimate user makes a properly authorized transfer of funds under the influence of the attacker.

This principle is stunningly successful. Globally, it represents 75% of all digital banking fraud losses on a dollar value basis—the lion’s share of digital banking fraud losses. In the US, 1 in 5 people lost money to imposter scams in 2022, $1.6 billion attributable solely to APP fraud. Meanwhile in the UK, APP fraud represented 41% of all fraud losses, or just under £250 million, in the UK in the first half of 2022 alone.

While the issue is global, two factors give the false impression it is a particularly US and UK problem. First is the ease of communication: The worldwide use of English means those markets can be and are targeted by scammers from around the globe. The other is rule of law: the US and UK have comparatively strong reporting and regulatory mechanisms, so not only are cases of APP fraud more likely to be reported, victims are more likely to get reimbursed.

To affected bankers, this might feel like a gross injustice. Those whose customers sent the funds in the first place are only following the properly authorized instructions of properly authenticated customers. In the case of banks receiving the stolen money, it feels even worse. In many cases, the stolen funds are with them for only a couple of minutes, making it easy for them to claim that they have no way to assess that the money comes from fraud proceeds.

But internet banking has been used for decades and the average bank user has become more digitally native during that time. So why has APP fraud become such a hairy problem now?

The real issue behind the dramatic increase of APP fraud is not the fraud itself, even as the creation of scams has been helped along by technology. Instead, the sea change in recent years has come from the ability of the attackers to quickly and easily launder the proceeds of fraud and extract them from a financial system without getting apprehended.

Instant SEPA transfers in the Eurozone, Zelle transfers in the US, sub-second transfers achieved by neobanks worldwide, and other payment innovations that have made our lives so much easier over the last few years have also made money laundering far easier. By the time a victim realizes that something is wrong, their money is already gone, having moved between several money mule accounts and ultimately to cash or crypto, usually by way of several banks in multiple jurisdictions. Every "hop" along the way means at most a few minutes to the attackers, but slows down any law enforcement action by weeks or months. The laundering process is often fully automated and overseen by fully remote workers, with most perpetrators acting abroad.

While this makes the money trail hard to follow for law enforcement, it explains why legislators in the UK—often the trailblazer market both in financial products and regulation—are looking to move the market from a situation where 80% of victims are voluntarily made whole by their own bank, to one where reimbursement is mandatory and shared with the institutions at the receiving end of the fraud.

That these recommendations are coming from the Payment System Regulator and on the heels of the Financial Conduct Authority's Dear CEO letter to payment firms and e-money institutions makes it plain that the fintech market is being strongly implicated.

Neobanks are already seeing the fallout of the reputational damage from APP fraud. My own traditional bank, for example, already blocks any credit card top-ups of my Revolut account. This is a strategic threat when your entire business model is based on disrupting the existing system with greater convenience. Nor is Revolut an isolated case: neobanks' perceived connection to fraud is increasingly being used as justification to blacklist them from participation in the broader financial system altogether.

But is this a fair assessment? Are neobanks really the problem?

Some numbers pretty emphatically suggest the idea that neobanks are significantly more risky than traditional banks.

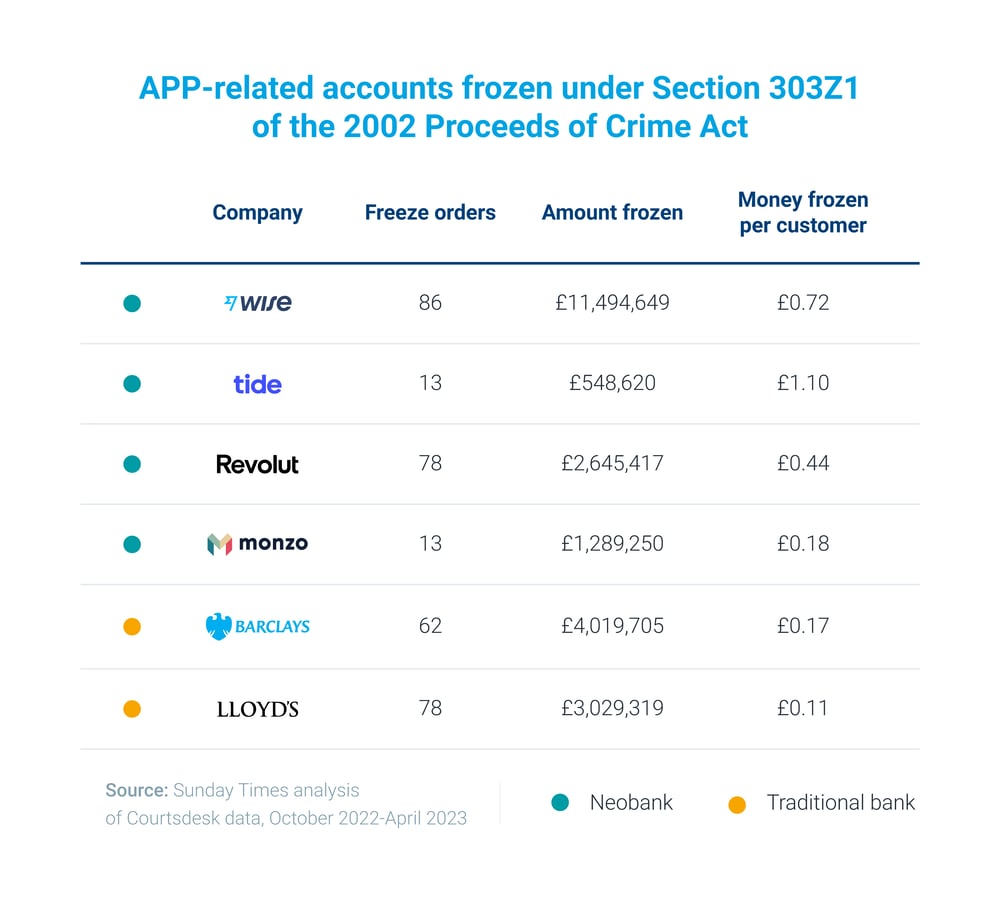

The Sunday Times recently published an exposé comparing fraud-related account freezes in neobanks and traditional institutions suggesting that a disproportionate amount of the accounts are held by neobanks (25% of the accounts with an 8% market share), and that there is a three- to seven-fold difference in fraudulent assets when normalized against the entire customer base.

So, case closed?

Well, as with any statistics, average numbers only give us part of the story. Most fraud concentrates in newly opened accounts, so you would expect a far greater concentration of fraudulent accounts in younger companies with a greater share of new accounts. Comparatively, most customers of traditional banks have been there for decades, and the customer base is significantly larger.

The damning revelation is that the number of frozen accounts across the different institutions in the report—new and old—are all in the same range, even though the older institutions will have had far fewer account openings over that time. But their larger denominator (total accounts) creates the illusion they are better insulated against fraud.

A fairer comparison would be to analyze fraud ratios over customer cohorts with similar tenures. But we need to go beyond statistics to see the real source of neobanks' perceived vulnerability to APP fraud.

A more relevant factor may make neobanks objectively more dangerous: their convenience.

The developers employed by criminals are like any other developers on the planet: they love modern, well-documented, and functionally complete APIs. Having good IT ironically makes you an oversize target in the financial world.

We argue that the APP fraud can be a major financial risk for any bank. And even more specifically, we mean the APP fraud committed against the customers of OTHER banks. As a bank leader of a forward-thinking institution with robust anti-fraud controls, you may sleep very well, knowing that your own customers are well protected. And you may wake up quite suddenly, realizing that the real risk is elsewhere.

Most current KYC processes are compliance driven: the bank verifies whether an onboarding customer is on any sanction list, can check for adverse media to identify potential past crimes or risks, checks for corruption risks by screening for political exposure. These are now standard processes neobanks have ported over into the digital onboarding experiences that traditional banks are often scrambling to adopt under competitive pressure.

But any bank, traditional or neo, can become a target if attackers can find a tiny gap in the KYC process for new customer onboarding. The attackers are using automation to systematically probe and discover even tiny gaps in the KYC process. They employ stolen, fictitious, or synthetic (a mix of stolen and fictitious) identities to onboard potentially hundreds of fraudulent accounts, which are then sold on the black market as synthetic money mules—accounts used once or a few times to receive and then forward the proceeds of APP fraud or other financial crime, or as exit accounts to withdraw the funds.

Digital onboarding turns the security game between the bank and the fraudsters into an iterative, learning game. Instead of only a few attempts to create fraudulent accounts in the physical world, attackers get an essentially unlimited number of attempts to defy the system. Instead of manually forging paper or plastic documents, attackers can create forgeries digitally. And instead of in-person probing, when each attempt may lead to arrest, the digital criminals are incrementally learning from hundreds of attempts and using all the explicit and side-channel feedback the bank provides—with essentially no personal risk. The attackers also rely on specialized criminals intermediated by efficient black markets—outsourcing to collectively learn even faster.

This is where the real risk is: relatively minor gaps in digital KYC onboarding processes results in money mule accounts—today disproportionately concentrated within neobanks as they are the innovators in the field. That concentration is mirrored in the risk of neobanks having to pay the second half of APP reimbursement far more frequently, as they are bound to receive a major portion of APP fraud proceeds. And this presents an existential threat to newcomers trying to hold on to their established footholds in the finance industry.

Some would argue that digital onboarding—and the increased volumes of fraudulent identities and scalable attacks that come with it—would require digital banks to increase the friction and selectivity of their KYC process by several orders of magnitude just to keep the risks on the same level. This is not so: instead of increasing the friction, we can use the existing data to address the scalable attack risks far more effectively.

This is exactly the game we play on behalf of our customers. The job of Resistant AI is to reliably defy scalable attacks using machine learning techniques that outsmart the attacker's technology. To do so, we can't rely on silver bullets; in the real world, no technology is bulletproof. Instead, we rely on scientifically designed interlocking defenses, where multiple independent layers progressively reduce the level of threat and cover each other's blind spots.

We view these layers in four general groups corresponding to four parts of the customer life cycle.

It's this combination of insights from identity documents, non-identity documents, digital fingerprints, and transaction monitoring that allows us to achieve very high detection rates—both for new customers and the already existing ones - and prevent the creation and scaling of synthetic money mule accounts. It's also what returns the initiative to the bank and turns the table on attackers. Being a well-defended sitting duck is rarely a winning strategy.

By spreading out reactions over the life cycle, fraudsters can never be certain whether the fraudulent accounts they have created within closely monitored banks have already been detected as potential money muling accounts or will be very soon. In turn, this uncertainty reduces their accounts' resale value on the black market: no APP gang wants to transfer stolen cash through accounts that are likely to be blocked the moment fraudulent proceeds reach them. The ability to effectively stop the proceeds of APP fraud is a strong deterrent for subsequent attackers. As soon as they start losing money, they will use sleeper mules in other banks.

For us, preventing the creation and use of money mule accounts that move fraud proceeds and then extract them from the financial system is the only effective way to reduce APP fraud. It breaks the business model of attackers, protects our client institutions from reimbursement charges, and preserves the low-friction financial services ecosystem we are building as an industry.