You might be interested in

I need a verified US account, how can I buy?

Hi sir available…

...We can deal with 50/50 amount..

...It’s better if you agree…

...We will build trust...

...Shall we proceed?

At Resistant AI, our Threat Intelligence Unit is focused on researching and investigating fraudsters as well as the marketplaces, ecosystems and infrastructure enabling financial crime on a global scale.

For example, we have been systematically tracking and cataloging template farms (specialized sellers fueling proliferation and distribution of high- quality, ready-made document templates).

We have also recently been exploring the “verified account” market, an ecosystem full of specialized vendors offering onboarded, active accounts for thousands of financial institutions and other companies across numerous sectors.

But our work is not just about monitoring, mining and exploring data.

We are also continuously embedding ourselves in fraudster communications, testing, and ultimately verifying our data-based hypotheses.

This time around, we decided to test the "verified bank account” market, simply because it wasn’t enough to “just” harvest and analyze without understanding how the crime works practically.

We found that these communities are very much real, and thriving in terms of activity and number of people involved.

So this time, we’ll take you on a behind-the-scenes look into how fraud enablers might communicate and how the account market might function overall.

Shall we proceed?

You bet we shall.

Before we walk you through our entire account buying experience, we need to establish the core concepts, logic, and reasoning for this research.

As usual for our Threat Intelligence work, we won’t disclose the name of any specific companies falling victim to account selling, or the virtual identities of the actors we were interacting with.

This is for two main reason:

Now that that's established, let's get started. First of all, who is actually selling these “verified” accounts? And what does the offering look like?

A “verified account” offering relates to vendors selling accounts that are already onboarded, active and have passed all required KYC checks.

These offerings are being routinely published by an “account farm”.

An account farm is set up by ”account farmers” in the form of websites, messaging app accounts or channels, social media pages, web forum threads, or any other channel, forum, or marketplace that allows direct communication with prospective customers.

Examples of account-selling on Telegram, websites and social media

Account farms dramatically lower the barrier to entry for sophisticated financial crime. Instead of investing time and risk into building mule networks, fraudsters can now buy accounts at scale, accelerating money laundering and other illicit activities while making detection and prevention significantly harder.

For several months now, we have been scouring the open web and various Telegram channels to observe, monitor and analyze as many account offerings as possible.

Our webinar on the account farming issue: Money Muling 2.0: Inside the Online Account Farm Economy is currently available. Read our summary or watch the recording to get a full-context picture of this threat.

But what’s actually in the “verified account” package?

Based on our own account purchases (so far), the “verified account” package usually contains:

Main components of the "verified account" package include account logins,

account-linked email logins and all supporting documentation

All three package components are essential, as you won’t be able to do much with just one or two. Bought account logins are self-explanatory, of course, but access to other linked accounts such as an email, a marketplace profile, or a social media pages are also important:

And, maybe most important, the documentation is needed at all stages of bought account handling, either for additional verification purposes or simply having all the details used for initial onboarding at hand.

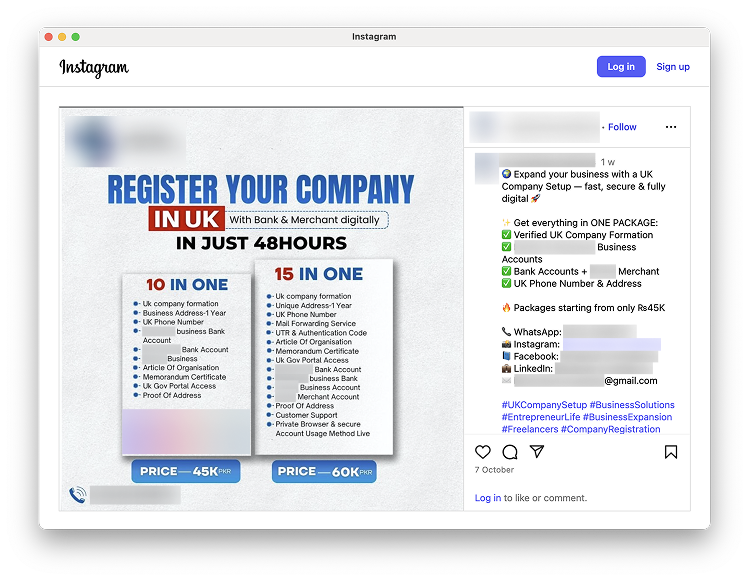

However, account farmers or fraud enablers in general do not stop there. We’ve increasingly seen some offerings implying that fraud enablers are pushing the package/service level to even further heights.

How?

A good example can be the selling of verified business accounts. In most situations (but not always, unfortunately, but we’ll get to that), you need an existing legal person to start these accounts. Account farmers won’t “just” give you the logins.

They’ll often provide even more complete service, including full company formation incl. provided identity and registered address, and an associate marketplace account creation (if it’s merchant-related).

Example of an expanded offering by an account farmer, including company formation and other associated services

Sometimes, they go even further and offer the provision of a fake company website or a merchant profile to paint a truly complete picture.

Sometimes, account farmers seem to go as far as to include website design or even

merchant profile creation into the "verified account" package

This further signifies why account farming is a significant piece in the “fraud-as-a-service” puzzle.

And it’s also why we try to focus on all individual components of the financial crime strategies: forged documents originating from templates, account selling and all the supplementary services that might come with it.

What our research has shown us is that financial crime enablers increasingly realize that their profit margins might be the highest if they supply an end-to-end service, leaving only one decision for the criminal: what crime to commit.

In short, this is not just about template farmers or account farmers. This is a constantly growing ecosystem of commercialized fraud enablers that make financial crime simpler, easier and globally accessible.

Our Threat Intelligence Unit monitors and estimates the size of these ecosystems and the results are always staggering.

With respect to the “verified account” market, we have another massive criminal enterprise on our hands.

Our estimates of the “verified account” market size are based only on the datasets we have compiled so far. Even with so much data already captured, we think we might still be just scratching the surface of a much larger network .

So far, we have identified and analyzed 100 different "account farm" websites with:

This is already a sizable market. But things get much more dire when it comes to our analysis of the account farming activity on Telegram.

After 1 month of analyzing Telegram communications within 55 different channels, we’ve already identified:

Once again – this is only a fraction of what is most likely happening on

a daily basis.

Why such a discrepancy between the website and Telegram high-level stats?

First of all, websites function as static online stores, meaning the buying and distribution process does not have to include any manual inputs or direct communication between the buyer and the seller. In that sense, account farming websites might be the farmer’s dream as it’s a highly scalable and potentially automated form of account selling.

But there is a caveat. As we’ve experienced during our own account purchases, trust is a significant factor in this process, and direct and instant communication between the buyer and seller establishes (at least some level of) trust. The average price of an account is around $350 and even (or especially) fraudsters do not want to be scammed and lose their money for nothing.

You’re not risking just a few bucks as you might when buying a template, and the financial stakes are much higher for the customers within the verified account market. You don’t want to enter your payment information on a website and just “wait and see”.

This is why we believe criminals prefer messaging platforms (which thrive on instant, direct communication) and they still get looped into most purchase flows, even when a customer begins his “buying journey” on an account farm website.

Let’s now move on to describing how we went about our own purchases, and what lessons can be learned from them.

As stated, we monitor a lot of channels where accounts are sold, and have seen hundreds of thousands of offerings unfold in only a few months.

Embedded in one of the more prominent channels with thousands of active users, we chose one of the many banking & payments account offerings , initially focusing on the purchase of a business-related account.

Why a business account?

We were interested in the entire package and not just the access.

That includes the supporting documentation which can be somewhat more extensive when it comes to company accounts rather than personal accounts. Both KYC procedures include personal documents such as IDs, but the business account onboarding also requires corresponding business documentation.

And what about our seller?

Farmers are not stupid, and they obviously do not disclose their real identities or locations.

Our seller is active in 3 of the channels we’ve analyzed, claims to be “selling premium business accounts as a 24/7 service”, and lists a French phone number on his profile.

He/she also seems to specialize in US and UK business accounts for numerous digital banks. But this is definitely not a case of the biggest or most visible seller. His profile was“ordinary” among potentially thousands of similar sellers. And that’s exactly why we tried to test this one out first.

Because if an ordinary, small-time account farmer could deliver, chances are high all these other account farmers can deliver as well.

Once we found our account farmer, we moved into a direct conversation.

We expect this to be the standard operating procedure, further explaining why most of the channels contained messages focused on selling and not buying, as these channels essentially function as some sort of marketplaces where farmers compete with each other while the transaction and distribution happens in private conversations.

Initially, our seller suggested we process the transaction using an “escrow” service, an intermediary that holds funds while a deal takes place.

Today, escrow has been fully digitalized, as online platforms often hold funds during e-commerce transactions, domain transfers, freelance work, and even cryptocurrency deals. Sometimes the escrow is even handled by an administrator of one of the “marketplace” Telegram channels we are monitoring.

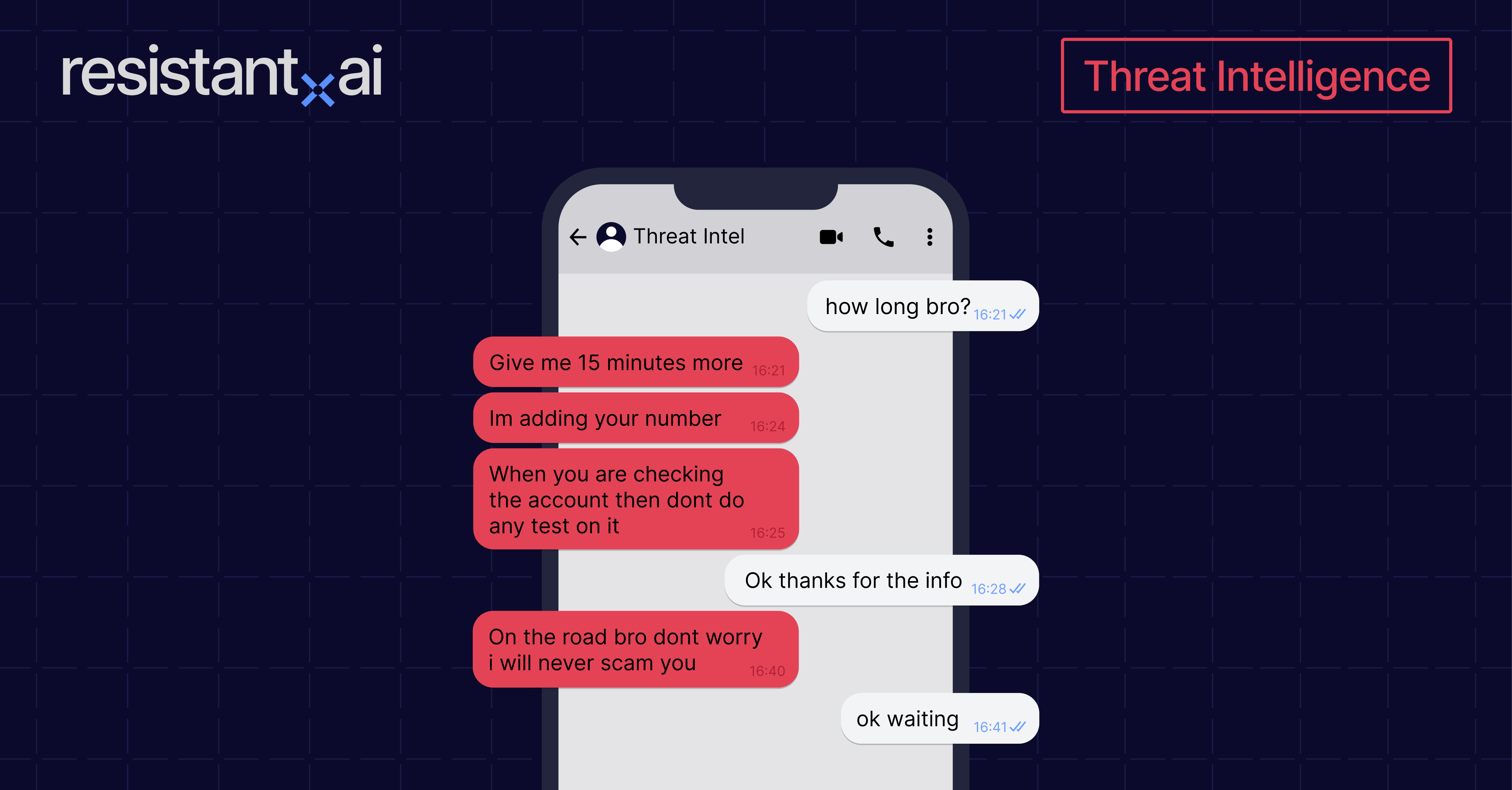

But we wanted to deal with our account farmer straight up, and without any middleman. After a few messages, we agreed on a “50/50” approach, sending half of the funds upfront and only providing the rest after we get the full package.

Imagine our concern when, after sending the first half of the money and the farmer confirming receiving it, he/she went silent.

“Did we just throw our money away?”

An hour went by, and we still didn’t even get our logins.

Asking our account farmer about the holdup, he/she seemed to be stalling:

Is there honor among thieves, as they say?

To our surprise, our seller sent us a photo seemingly taken from a scooter bike stuck in a traffic jam. Some basic OSINT then placed the seller in a large city in an Asian country.

Was it really a genuine photo? Did the seller not mind if we knew where he was?

It seemed to be the case as, about 2 hrs from our initial transfer, the farmer used our provided phone number to start the account handover.

Bro…

…sending OTP…

…ready?...

Unfortunately, right after the handover seemed to have finally started, there was more stalling:

Was this really the case? Again, we were forced to wait and see.

3 hours after the initial purchase, things started moving.

We quickly learned that the initial step in the handover process is the switching of the account-related phone number. As verification through phone is the standard and often used procedure, the account farmer needs to ensure the phone number switching is efficient (and that the change confirmation is completed right after the OTP sending).

Once the phone was switched, we moved to the login handover phase.

Our seller sent us both the purchased account logins and the associated email logins.

And we did log in. Confirmed login via both phone and email. Case closed.

Funnily enough, the roles switched once we received the logins, and it was now the account farmer who was impatient to complete the deal.

As stated before, we wanted to review the full package, and we did send the second half of the money.

Soon enough, we received some documents, including:

Reviewing the documents, it quickly was clear these were all fakes.

What was even more alarming, the company itself did not even exist when checking its name in the business registry where it should be filed, meaning this platform had already onboarded a fraudulent company.

But at this point, there was no reason for us telling that to the account farmer, or further engaging in hassling over the documentation provided.

At the end of the day, the account was live, and we had control over it.

Now, we get to the most interesting (and scary part) of our entire account purchasing adventure.

What does all this mean for financial institutions (and other businesses) across the globe?

The first and main outcome of our account purchase is the validation of the fact that at least some (if not most) of these account offerings are real.

Previously, there could have been a notion that the account farming and selling activity could just be another scam – extract the funds, send bogus logins, and cut off communication, case closed. In fact, some financial institutions even claimed this to be the case, trying to downgrade the verified account selling threat altogether.

Not anymore.

Considering some of the high-level stats we mentioned above, even if only a half (or even) less of the activity we’ve tracked over 1 month proved to be real, the account farming activity would then still be a major threat.

And we know there’s more channels, more sellers, and more accounts being offered on a daily basis across the world, in different languages, and to anyone who wishes to purchase one.

In short, this threat is very real, and financial institutions need to react accordingly.

How?

Everything starts with understanding how exactly account farmers breach KYC and onboarding processes.

We’re at a point where even extensive documentation requirements (IDs, business documentation, questionnaires etc.) do not guarantee security. One successful breach and an account farmer “figuring out the formula” then only guarantees repeated attacks.

Using forged documents, leveraging AI generation, or even setting up entire shell companies, fake websites or merchant profiles, the palette of tools and assets provided by professional financial crime enablers is only getting wider and more diverse.

But more on that next time.