Money Muling 2.0: Webinar Recap

Money muling is taking on a new form in 2025. Where fraudsters once relied on coercion, deception, or shady recruitment schemes, they now have a more powerful tool: "account farms" that sell pre-authorized bank and payment accounts — effectively giving fraudsters an on-demand mule network at scale.

Our Director of Product Marketing, Joe Lemonnier, and Threat Intelligence Liaison, Jan Indra, unpacked the rise of these account farms in our recent webinar: Money Muling 2.0: Inside the Online Account Farm Economy.

If you missed it, please don't hesitate to...

Otherwise, keep reading for a clear overview of how the illegal account selling market works and why it matters.

What is an account farm?

An account farm is a website or messaging channel that specializes in selling pre-authorized, fully onboarded, and verified bank or payment accounts. In other words, they provide criminals with ready-made personal or corporate accounts to use for financial crime.

Account farms dramatically lower the barrier to entry for sophisticated financial crime. Instead of investing time and risk into building mule networks, fraudsters can now buy accounts at scale, accelerating money laundering and other illicit activities while making detection and prevention significantly harder.

Our standard definition of "account farm" from the webinar.

How are these accounts created?

In order to sell accounts, fraudsters first need to create them. This typically happens in one of two ways: as consumer accounts or as business accounts, both of which involve navigating and exploiting KYC (consumer account) or KYB (business account) processes.

- Consumer accounts. Personal accounts set up to look like legitimate users and bypass KYC checks. Criminals rely on three main tactics:

- Fake person. Using invented identities that appear real enough to pass initial checks.

-

- Synthetic identities. Combining stolen and fabricated data to build a new, seemingly authentic persona.

- Account takeovers. Hijacking an account by hacking or stealing a person's information.

- Business accounts. Business accounts are often more powerful since they can handle larger transaction volumes and may be subject to lighter scrutiny in some systems. Fraudsters may:

- Create a fake company from scratch. A forgery-heavy activity due to the extensive mandatory documentation

-

- Register a shell company. This company might not have any real activity behind it. It can include forging some documentation, or it may be legitimate documentation that bypasses basic registry checks.

-

- Take over a real company. This can be easier than compromising an individual. All you need is the right documents to claim ownership of a business (articles of incorporation, business license, etc).

Fake documents

No matter how fraudsters open the account, fake documents are typically involved to satisfy KYC and KYB checks. This ranges from manipulated IDs and doctored utility bills to fabricated incorporation papers and tax filings.

Methods vary from simple PDF editing tools to advanced image editing and fully AI-generated documents. Template farms are also readily available online with a simple Google search, selling ready-to-edit official document layouts for criminals to modify.

Stolen information and synthetic identities

Data breaches, leaks, and large-scale credential dumps have created a vast supply of personal and business details for criminals to exploit. With this information in hand, account farms can assemble fake bank accounts by blending authentic data points with fabricated ones, producing synthetic identities that appear genuine enough to pass standard KYC or KYB checks.

The challenge for defenders is that these real, stolen details (like an actual social security number or date of birth) can pass verification when checked against official registries.

With so many massive data leaks, these criminals have an endless resource for creating identities in hundreds of different variations that even official registries fail to catch them. The only way to spot this kind of fraud is to assess the legitimacy of the documents themselves.

Liveness and selfie checks

Many financial institutions and payment platforms rely on liveness or static liveness (selfie) checks as a safeguard against fraud. Rather than just uploading a document PDF or photo of an ID, users are asked to take a live selfie or perform small movements to prove they are a real person.

In theory, this should prevent fraudsters from opening accounts with stolen or fabricated identities. In practice, account resellers have found ways to work around these controls.

For static liveness checks, criminals are doctoring images and swapping faces so the ID and the selfies match.

For the moving iterations, it's a bit harder to pass, but not impossible. Criminals inject deepfake techniques to patch together moving faces and trick automated systems.

In other words, even the most sophisticated onboarding protocols can still be exploited.

Who is creating the account farms?

Our own findings point to the fact that many of the same actors who once focused on document forgery (the template farm marketplaces that sell counterfeit IDs, proof of address, business registration documents, and more) are moving up the value chain into the account selling business.

A map of referring domains connecting account farms to template farms.

With the infrastructure already in place, it’s a logical next step. After all, selling raw materials like fake documents generates profit, but bundling those materials into verified, pre-authorized accounts commands a much higher price.

We’ve already discovered several template farms with millions of monthly visitors, which means they already have quite the market to sell to.

By combining their existing capabilities to mass produce fake documents with large data leaks and automation tools, they can test and iterate against institutional risk controls, creating fake accounts at scale.

While the term “well-organized” is often associated with money laundering networks, these account farmers appear as anything but “organized” in practice. They operate in chaotic social marketplaces with competition at the forefront. Visit one of these Telegram channels and you’ll be bombarded with hundreds of competing offers, a frenzy of criminal solicitation, built from the same resources but aggressively competing for your business.

This creates a stark contrast between the reality of these marketplaces and the larger money laundering ecosystem that they're fueling.

According to FATF research, professional money laundering networks have become highly specialized, offering infrastructure and expertise to anyone who needs to move illicit funds. The account selling marketplace, on the other hand, doesn't appear organized or willful. Instead, it's like the wild west: a conglomeration of opportunists with new technology and tactics at their disposal, eager to capitalize and make a quick buck.

Why we think account farms is a logical next step for template farmers.

How are accounts distributed?

Once created, accounts have to be sold and delivered, and criminals rely on two primary distribution channels: encrypted messaging platforms and standalone websites. Messaging platforms are nothing new in the world of cybercrime. They are mature, well-developed spaces where escrow services and direct negotiation are already standard.

What is new, however, is the emergence of:

- Social media advertisements.

- Document hosting sites (like Scribd & Pinterest).

- Standalone websites.

These sites mimic e-commerce shops with product listings, prices, and promises of “verified” or “onboarded” accounts, brazenly advertising in public spaces with seemingly little concern for subtlety.

Likely inspired by the rise of template farms, they reflect a bolder, market-oriented approach aimed at siphoning off mainstream internet traffic. Some of these template-farm style sites attract millions of monthly visitors, employing the same SEO tactics that legitimate businesses do (like keyword stuffing and interlinking content), and account-selling platforms appear to be following the same playbook to broaden their reach.

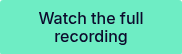

Why messaging platforms are critical in the purchase process

For now, messaging platforms remain a critical step because of the “handover problem,” where sellers need to directly transfer control of an account to the buyer. Direct communication to swap out personal details (such as linked phone numbers or recovery e-mails) is difficult to automate. Sellers need to share the codes immediately, exchanging phone numbers and one time passwords, a speed that’s difficult to achieve via an online form or other entry point.

However, criminals are always working towards better automations and just because it hasn’t been achieved at the domain level yet doesn’t mean they’re not currently working on a solution (or have already developed one that we didn’t discover).

Telegram’s anonymity and large scale chatrooms make it a digital bazaar, but the experience is fragmented. Groups appear and disappear quickly, listings get buried under constant chatter, and the process of buying accounts is messy.

This volatility complicates enforcement, yet it also creates friction and difficulty for consumers. This opens an opportunity for account farms to move onto websites where they can offer a smoother, more professional storefront to capture larger volumes of traffic.

Account buying process

Here’s how the account buying process typically works:

- The offer. A buyer sees an offer for accounts, usually posted on a website or in a messaging group, and reaches out to the seller directly.

- The deal. The two parties agree on a deal, and an initial portion of the payment is sent, often through privacy-preserving methods (like cryptocurrencies or other hard-to-trace digital payment options).

- The transfer. Once funds are received, the seller begins transferring control by updating the account phone number or authenticator to one controlled by the buyer. Then the buyer shares the one-time-password (OTP) with the seller so they can complete the changes.

- The test. The buyer is then provided with the login details to test access to the purchased account.

- The payment. After confirming that the account works, the buyer sends the remaining payment.

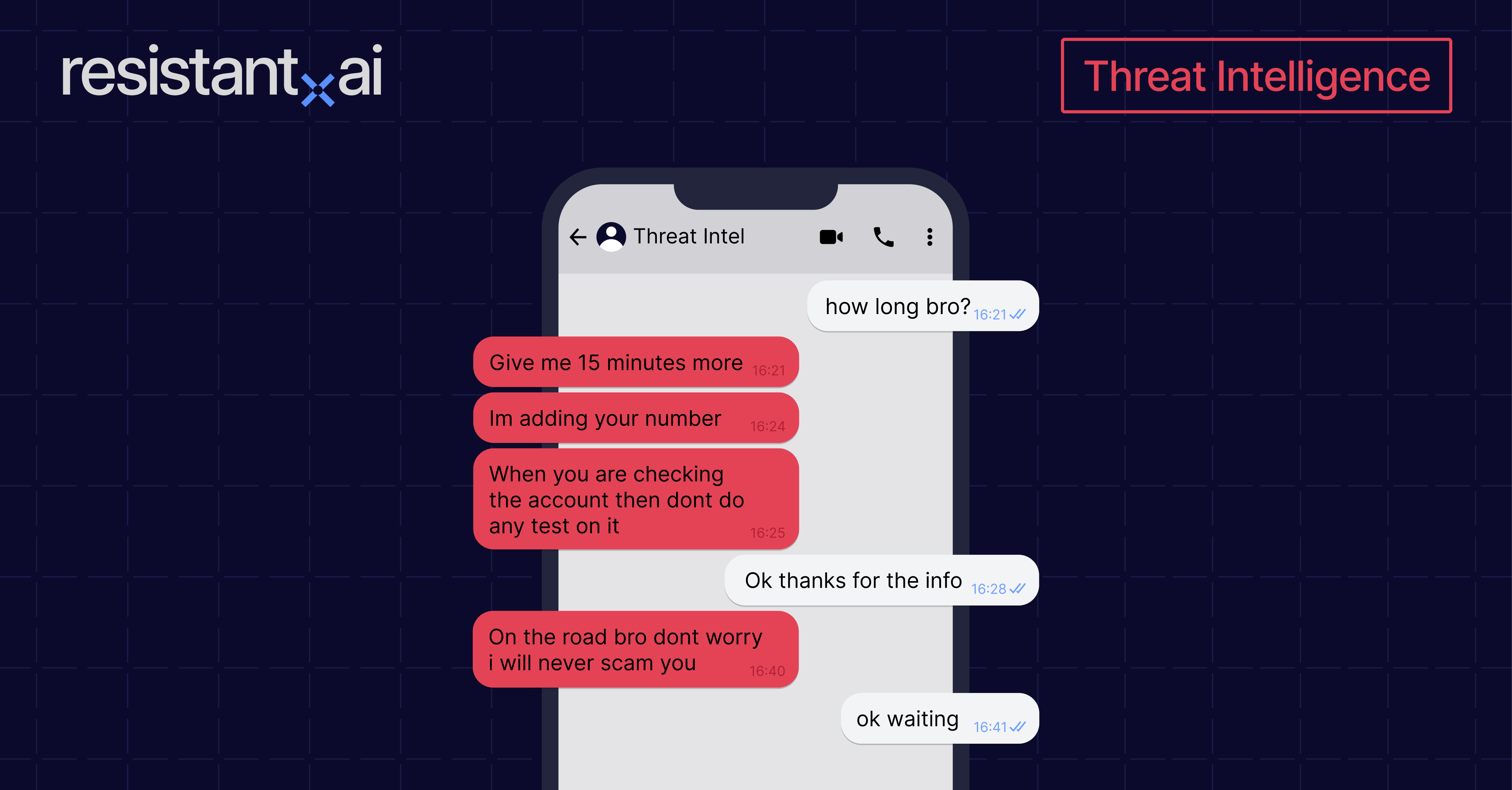

- The package. Finally, the seller delivers the rest of the “package,” which can include supporting identification, proof of address, proof of income, or source of wealth documents or business records that make the account appear legitimate.

The typical contents of an account purchase package.

The role of escrow

In these transactions, neither side fully trusts the other, so an intermediary holds the funds until both parties meet their obligations. This is called escrow. For account farms, this reduces the risk of buyers disappearing after gaining access to an account or sellers taking payment without delivering anything of value.

On Telegram, this process is made easier by the way groups and bots handle transactions. Many fraud-focused channels set up their own escrow services, where an admin or automated bot holds the buyer’s cryptocurrency until the seller proves the account has been handed over. Instead of needing to trust each other, buyers and sellers can lock funds within the platform until the deal is confirmed.

How big is the account selling market?

In just a month of research, our Threat Intelligence team identified more than a hundred standalone websites and dozens of Telegram fraud channels promoting fake bank accounts for sale.

Remember, this was just a snapshot. Out of the millions of Telegram groups that exist, we only sampled a few dozen English-language channels (a tiny slice of the ecosystem), yet even that limited window revealed a booming (and probably much larger) market.

Within those channels, the activity was constant: thousands of unique messages, many of them automated through bots, kept the flow of offers alive around the clock.

Among the accounts for sale, thousands of different banking and payment platforms were available (from mainstream financial apps to niche services), and the total number of accounts for sale easily ran into the hundreds of thousands.

90% of the messages we found were from sellers promoting their illicit bank accounts, but that doesn't mean the channels are empty marketplaces. They are storefronts where buyers pick products, and the transactions occur in private messaging sessions away from prying eyes.

How much does it cost to buy a fake account?

On average, a fake account sells for about 344 USD. The range is wide: some accounts can cost more than $2,000, while other offerings (likely scams) can go for less than $5. This variation reflects both the type of account on offer and the effort required to create or compromise it.

More costly price points could indicate a seller that doesn't have a scalable, systemic way to produce accounts and instead relies on more manual, one-off methods.

The account price can also reflect the platform itself. If a bank or payment service has stronger onboarding controls, or has slower and/or manual processes that don't lend themselves to automation, verified accounts become harder or slower to obtain, constraining supply and increasing prices.

Another factor is the account type. Buying a consumer account is cheaper than a business account given the additional documentation and controls involved. If you want some financial history as opposed to a blank one with no transactions, that will also cost you more.

.png?width=3200&height=1800&name=WEBINAR_DECK_Money_Muling_2_0_SCATTER_PLOT_account_farm_TELEGRAM_1%20(2).png)

Range of account purchase price vs. number of offerings listed.

Who is most vulnerable to account selling?

We have seen more than 3000 different institutions affected. Each compromised or fabricated account becomes a gateway for fraud, compliance failures, and money laundering. When multiplied across thousands of services, the result is systemic risk.

Despite the sheer size of the market, many institutions still aren't sure if their platform is affected (according to the polls we ran during the webinar):

Poll #1: The majority of our attendees weren’t completely sure if their accounts are on the market.

Want to know if your institution is being targeted by an account farm?

Industries impacted by account farms

What types of institution are affected among this 3000+? Account farms are a cross-sectoral, cross-segment issue. Here are the sectors that stand out:

The distribution of industries affected by illegal account selling.

- Banking and payments. These accounts can be used to move illicit proceeds into the mainstream financial system, making dirty money appear legitimate. Criminals may use these accounts to route or disguise transactions, cash out stolen payment cards, or test fraudulent activity at scale.

- Traditional banks. Legacy financial institutions remain a prime target because of the volume of funds they handle and the trust they carry. Traditionally more acquainted with in-person checks, the increased friction (not necessarily better risk controls) in their digital onboarding can sometimes make it harder for criminals to scale their account creation: it's not as easy to automate back and forth email communications at scale.

-

- Payment firms and neobanks. Built for speed and convenience, digital-first banks often emphasize frictionless user experiences. They onboard users in minutes to their expertise in this space, but it doesn’t mean their controls are weaker compared to the digital channels of traditional banks that take days or weeks to do the same. But that frictionless process lends itself to adversarial manipulation and automation that can scale account creation quickly when a weakness is found.

- Exchanges. These are the financial firms that help customers buy and sell assets such as foreign currency, commodities, or securities. Handling large transaction volumes and interacting with multiple counterparties, they are an attractive place to hide illicit funds. Bad actors move money rapidly across markets, obscure its origins, or engage in practices like wash trading to create the illusion of legitimate activity.

- Crypto platforms. Fake or compromised accounts on these platforms are especially valuable because they give criminals a way to swap funds across multiple tokens or chains, move through tumblers, cross-chain exchanges, and personal wallets, making the opportunities for layering exponential. By serving as both the entry point for illicit money (placement) and the place where that money can be converted back into seemingly clean assets (integration), crypto platforms give criminals a one-stop shop for all three stages of money laundering.

- Marketplaces. Online marketplaces are attractive targets because accounts can be used to facilitate fake listings, launder proceeds through sales, or gain access to buyer and seller payment information. Criminals value them both for direct fraud and as channels to cash out. Accounts can also post fake reviews of products, boost ratings, or bomb competitors.

- Remittances. Money transfer services such as wire providers or remittance apps often have strong checks when money enters the system, but the receiving end can be a weak spot. Lower KYC requirements for recipients make these platforms a convenient way to offload illicit funds.

- Social media. Accounts with large followings offer credibility that criminals can exploit. Once compromised or fraudulently created, they can be used to advertise scams, manipulate marketplaces, or trick users into sending money. Fraudsters also use social media marketplaces themselves to run illicit schemes.

- Work tools and tech infrastructure. Business software and productivity platforms (from email services to project-management tools and cloud storage) are also at risk. Fake or stolen accounts here can be used to impersonate employees, spread malware, or harvest sensitive data. Because these platforms often connect to payment systems or corporate networks, they can become stepping stones for larger fraud schemes or even full-scale intrusions.

Jan and Joe talking about what industries need to look out for illegal account selling.

How have these account changed money muling?

At their core, these accounts give money-muling a new look: no recruiting, no middlemen, no reliance on vulnerable individuals. Depending on people who are naive, desperate, or willing to lend their identity is risky. It creates loose ends, it's hard to control, and difficult to scale.

With account farms, a fraudster can buy a ready-made account and start moving money instantly, entirely under their own control.

By routing illicit funds through multiple accounts, often across different platforms and jurisdictions, criminals obscure the origins of their money and frustrate investigations (i.e., “layering”).

The specific type of account also shapes how it can be exploited. A dormant consumer account might be sufficient for quietly moving small sums of money, while a fully verified business account with several transactions already conducted can be leveraged for larger payouts.

The key shift is scale. Document-selling markets gave criminals raw materials (IDs, certificates, and templates) but account farms go a step further. They offer finished products that can be used for financial crime immediately.

With thousands of accounts available and no human mules to manage, fraudsters can run operations at an industrial level, recycling accounts as they burn out and keeping the cycle going without pause.

How money mule account farms power APP Fraud

Authorized push payment (APP) fraud is a scam in which victims are tricked into sending money to criminals directly through authorized push payment apps.

Two years ago, we published a dedicated white paper on APP fraud & money mules, highlighting how the scale of the campaigns targeting consumers and businesses around the world implied a vast supply chain of money mules. Our research today confirms the existence of this infrastructure for multi-billion-dollar fraud operations.

At a small scale, APP fraud might involve a handful of intermediaries. But the level of fraud we see today (spanning countries and costing billions) would be impossible without ready access to thousands of accounts. Fraudsters cannot rely on recruiting three or four willing mules to power an operation of that size. They need industrial-scale infrastructure, and account farms supply it.

By making accounts instantly available, these networks have removed the natural bottlenecks that once limited financial crime, fueling the surge in APP fraud in recent years.

What other crimes do account farms enable?

Beyond APP scams, fake and mule accounts fuel a wide range of other illicit activity:

- Mule networks. Large numbers of low-value accounts make it easy to shuttle criminal proceeds through countless intermediaries, overwhelming monitoring teams and obscuring the money trail. This raises the risk of missed suspicious activity reports and regulatory penalties.

- Bust-out schemes. Fraudsters can build credit histories with fraudulent accounts, take out loans or overdrafts, and then disappear, leaving financial institutions to absorb the losses.

- Loan and credit fraud. Compromised consumer or business accounts give criminals a foothold to apply for mortgages, credit cards, or small business loans under false pretenses, exposing lenders to bad debt and reputational damage.

- Using other platforms to bypass controls. Fake accounts on lightly regulated services can serve as “on-ramps” into more tightly controlled banks or payment providers through Open Banking/PSD2-style API KYC checks.

- Account farming at scale. Some groups use existing stolen or synthetic identities to generate even more accounts, creating a self-perpetuating supply chain that expands the infrastructure available for laundering.

How to protect yourself from account farms and fake accounts

Stopping illegal accounts from entering and committing crimes on your platform requires more than a single line of defense. You need to leverage all of your layers of defense — everything from document reviews, behavioral and device signals, identity and entity details, and transactional details — all play a role.

The poll below shows how fraud professionals (who attended the webinar) have spread out their defenses into these different layers:

Poll #2: As you can see, many of our attendees put heavy emphasis on "ID verification" and "KYC screening." Companies should put more focus on Non-ID document verification as there might be a higher probability of low quality fakes.

What to look for at onboarding

At onboarding, you need to spot key warning signs of an illegitimate account:

- Fake, forged, or generated proof of address or proof of income documents. Don’t only verify IDs. Criminals often expect companies to put less efforts on the other supporting documents, which sometimes means low hanging fruit.

- Template farmed documents. Many account farmers are tied to the online account farms producing these onboarding documents. Check against these illegal catalogues.

- Repeated use of documentation across accounts. We call it “serial fraud.” Once you have a digital document it's very easy to edit it and make copies. Similarities among these submissions can be a clear sign of tampering.

- The company or person doesn’t exist in official registries. An essential first step that’s often missed and will clearly indicate a fake.

- Variations of the same company name in your platform. Fraud LTC, Fraud Pro LTD, Fraud Inc. — Similar company names within the same system can indicate linked illegitimate accounts.

- Abnormal behaviors: account creation times, security answers, and more. Accounts created one after another, from the same location, around the same time of day, with the same devices, repeating security answers, etc.

Of course, many of these warning signs can be checked in-house. But doing it manually is where the problems start. At scale, thousands of documents and accounts flow through onboarding every day, and no human team can realistically spot every recycled template, forged proof of income, or suspicious pattern in account creation.

Even well-trained analysts make mistakes under pressure, and rule-based checks quickly get outpaced as criminals change tactics.

After onboarding

Once criminals get into your systems, you have two types of accounts to be aware of:

- Dormant accounts. A fresh account with no activity tied to it. Easier to spot. Opening an account and doing nothing for an extended period is unusual and should be flagged for review.

- Active accounts. An account that has consistent activity. Harder to spot because they will fabricate activity to mimic legit accounts.

Signs your system may already contain these accounts include:

- Cycling. To give a history of behaviors, criminals will transact the same amount of money across the same group of accounts they control. This can include purchases from fake marketplace listings.

- Phone or email changes. This is the key indicator to look for, as tied with the others signals or a dormant account, it is the sign than an account is being handed over. Frequent changes to these fields in user data can indicate reselling.

- Sudden balance outflows & inflows around the changes. Sudden changes outflows before the changes in phone or email, and sudden inflows from a new counterparty right after are the tell-tale signs that the sellers are moving their cycling money out of the sold account, and the new owner moving their money in.

Why layered defenses are no longer enough

We've been the first to preach about how a single layer of defense is not enough, and that sophisticated crime needs different layers of defense. In fact, our own models are built in that fashion, each actually composed of layers of different AI techniques examining different signals, collectively feeding into another layer that produces a verdict.

But to stop the threat of account farms, it's not enough to have layers that are hyper-specialized and automated. All of the layers of you risk tech stack need to communicate, learn from one another, and adapt.

You need to be able to collect data from your entire risk stack and make sense of it at an enterprise level. By leveraging data from documents, behaviors, devices, identities, and transactions, you start piecing together a clear image of the threat itself and how to defend against it.

Here's what this looks like in practice.

Each of those dots (red, blue, purple, pink, and orange) represents clusters of accounts tied together by the reuse of a common document (the “serial fraud” we mentioned earlier). Colored lines then indicate further connections between these clusters corresponding to:

- Common transactions (white).

- Registration IP addresses (pink).

- Account creation dates (green).

- Mobile phone numbers (blue).

- Matching passwords & security answers (yellow).

Begin following the breadcrumbs, start matching all these data points together, and you will reveal that these four or five groups trying to breach your system are actually one entity, putting money in and using these different clusters as a means of spreading it around.

This is beyond the capability of human reviewers, and trying to do this with rules is unrealistic. This is a problem of scale and constant change that only AI can really empower risk and compliance teams to fight back.

How Resistant AI can help

This is exactly the kind of threat Resistant AI was build to stop — the kind of threat we predicted.

We already offer models that are focused on the document and transactional challenges, and they’re already capable of talking to each other: continuously informing one another to grow and improve.

But that's just the tip of the spear.

Resistant AI can leverage the signals from the rest of your risk tech stack, and even your basic digital infrastructure (timestamps, logs, etc) to build a complete map of the fraud happening within your system, catching lone occurrences, and, if they’re linked together, revealing those connections to build a more holistic defense.

The existence of these large scale marketplaces is proof that the old ways of doing things are failing us. Even with dedicated internal resources, building these kinds of defenses is no longer a side project, but something that requires dedicated AI and fincrime expertise. It needs true AI fraud and fincrime detection.

Want to see what's possible?

Talk to one of our experts today

Frequently asked questions (FAQ)

Hungry for more account farm content? Here are some of the most frequently asked questions about illegal account selling from around the web:

What is an account farm and how do criminals use it?

An account farm is a website or messaging channel that sells pre-authorized, verified bank or payment accounts. Criminals use these fake bank accounts for sale to launder money, commit fraud, or run scams at scale without relying on human mules.

How are fake bank accounts for sale created online?

They are created either as consumer accounts or business accounts. Fraudsters use synthetic identities, stolen data, fake documents, or even shell companies to pass KYC/KYB checks. Some accounts also come from account takeovers of real individuals or businesses.

How much does it cost to buy a fake account on Telegram?

On average, fake accounts sell for about 344 USD. Prices can range from as high as $2,000 depending on the platform, the type of account, security standards, the friction in place, and the speed of account creation.

What is the connection between account farms and APP fraud?

Authorized push payment (APP) fraud relies on quickly moving money through multiple accounts. Without account farms providing thousands of ready-made accounts, APP fraud could not operate at its current scale. Illegal account selling is the hidden infrastructure that enables these scams.