Doc Juicer – Uncovering a farm with 18k+ templates

In the first article created by our new Threat Intelligence Unit, we looked at Utility Bro, a template farm specializing in high-quality utility bill templates.

While such a farm undoubtedly presents a threat, it is an example of one that has a specific specialization, and focuses on quality rather than quantity. Not that we couldn’t detect such fraudulent templates anyway.

But in the business of document templates, as in any other, there are a lot of different strategies and approaches you can take.

And as many other ventures have proved over time, focusing on quantity might often be the way to go.

With that, let us introduce you to Doc Juicer aka a template farm on steroids.

While Utility Bro listed a measly 420 templates in its catalog, the story is entirely different here, as Doc Juicer already offers more than 18k templates on its website.

Summary

Why size matters

Doc Juicer’s massive template catalog is its defining feature, showcasing not only its ambition but also the level of resources and organization behind it. To offer such an extensive selection, certain facts are clear:

-

significant time and resources must have been invested in building and maintaining the template database,

-

this scale of operation also implies a team effort—editing, archiving, managing, and distributing such a vast collection isn't feasible for just one or two people,

-

maintaining infrastructure, web presence, and global distribution channels requires a well-organized, experienced group.

It’s evident that Doc Juicer’s goals are to provide something for everyone, aiming to capture the broadest possible customer base and dominate the template-farming market.

He wants to be the biggest marketplace out there.

The most well-known one, the one with the biggest audience.

The one that matters and commands respect even amongst other template farmers.

And from the standpoint of fraud defense and prevention, we need to pay attention to this for two main reasons.

First, as even one cheap template can be replicated a thousand-fold and be used for mass fraud attempts at hundreds of institutions, the existence of such a vast marketplace sends a clear signal — once you know where to buy, you can buy it all, and scale your fraudulent activity to heights you might not even have thought possible before.

Second, factoring in the hypothesis of Doc Juicer being a seasoned and organized template farm veteran, this means that the farm will be adequately protected, its content safely backed up elsewhere, and the possibilities of law enforcement taking the farmers down will be quite small due to the high level of organization and existing experience.

Doc Juicer is a big problem. And so we dug in.

Introducing Doc Juicer – the largest farm on record

So how did we find Doc Juicer?

Through an ad on a different template farm, of all places. Nothing like a friendly referral, right?

While we already briefly teased the interconnectedness of these farms, right here it presented itself to us in full light. The question of “if some of these farms are connected” quickly turns to “how connected are they,” and what actionable insights we can derive from it.

But let’s get back to Doc Juicer.

Over 18k templates and 50+ template categories, dwarfing many other farms we found so far combined.

But before we dive in the data, let’s look at the farm website itself first.

What does the farm website look like?

On the surface, Doc Juicer could look like any other regular template website providing “free editable templates” (think sites like Canva, Freepik or many others):

-

a header with contact links and template categories,

-

a product grid,

-

an FAQ section,

-

a footer with some QR codes, payment methods and even listing the HQ address, opening hours and a seemingly incorporated company name.

But that’s where the similarities end, as the templates being peddled here are utility bills, bank statements, passports, payment cards or a list of “real bank transactions” — anything you would need to commit fraud or financial crime.

Doc Juicer even sets its product grid filter by order of popularity to let its audience know which templates really matter here (hint: not resumes or business plan templates).

Like many fraudulent document template farms, Doc Juicer tries to provide a laughably weak example of a “legal disclaimer,” stating that its templates can only be used for entertainment purposes and “according to the letter of the law,” referring users to terms of service. Not that there actually are any terms located on the site, of course.

Many comms, but one platform dominates

The site lists 6 different communication channels, using platforms such as Telegram, WhatsApp, Skype, Viber or Facebook Messenger.

These are primarily used for ordering and distribution of templates, or for sending in special requests — Doc Juicer is happy to edit the templates for an extra fee, citing its “support team”.

It’s likely that some of the channels, notably Telegram, are used as the primary messaging platform as it allows for a higher level of encryption and user anonymity, while also allowing for easy creation of private or invite-only channels, bot integration for automating sales and orders, and even integrating an “escrow service” that facilitates the transaction between a buyer and seller.

It remains to be seen whether the popularity of Telegram will be in any way influenced by the current situation of its CEO Pavel Durov and the platform itself.

How template farmers make use of common review sites

But the most interesting aspects of Doc Juicer’s website itself revolves around customer feedback and interaction.

While Utility Bro shared snippets of direct communication with the customers, Doc Juicer employs a more typical e-reputation strategy that points visitors to well-known review portals like Trustpilot, ReviewFoxy, or Sitejabber.

Just like regular e-commerce services, this increases its visibility and improves organic traffic, as backlinks from global review portals significantly helps to rank high in search results.

But most importantly, it aims to create consumer trust and confidence via social proof, but things get a little tricky here, as some reviews flat out warn that “the farm is a scam” and they did not receive ordered templates, while others praise the farm for “its great service and team support.”

Figure 1: Examples of Doc Juicer’s reviews posted on well-known review portals.

Details were altered to preserve confidentiality.

It wouldn’t be surprising at all if template farms themselves planted some of these positive reviews, as is unfortunately the case with many other digital or social media “strategies.”

Regardless of whether Doc juicer occasionally scams its customers (honor among thieves, and all), as a purveyor of templates, it’s a legitimate target of our threat intel operations.

And we do see examples of its templates being routinely submitted to the doc processing workflows of our clients.

Even if the same template originated in a different farm and Doc Juicer “only” stole or replicated some parts or the entirety of the catalog, that still makes them a distinct part of the tapestry of fraudulent document providers that our threat intel efforts aim to unravel.

How Doc Juicer harvests even more templates

One important aspect of Doc Juicer’s site that we have not seen elsewhere yet is that it is actively trying to buy scans of current documents from its customers.

In essence, this would mean Doc Juicer is not only selling templates to potential (and likely) fraudsters, but it’s relying on those customer relationships to harvest more documents to templatize, becoming an originator of new templates and creating a vicious circle of criminals helping (and paying) each other.

After all, compiling such a large catalog of templates seems a lot easier when criminals join forces. Crowdsourcing of this sort likely drives faster template production, higher variety of templates, and further knowledge sharing between fraudsters and fraud enablers.

Considering the emphasis Doc Juicer places on looking for scans of current documents, the crowdsourcing aspect is potentially also the main factor behind keeping the template catalog updated and relevant as document issuers themselves routinely refresh their document layout or visuals. Tracking such document changes is a lot easier when you have an army of pawns supplying you with fresh documents.

But that’s just Doc Juicer on the surface. Let’s dive into some data.

How and when was the template farm launched?

This farm’s website origin story is a little tricky, as it seems to have changed its top-level domain (TLD) repeatedly over time, however keeping the previous TLDs that now function as a redirecting URLs.

The farm itself states that it “launched its website in 2015”, however, we traced back the oldest of these TLDs to November 2019 and the web archive screenshots as far back as January 2021, although available web archive data from that time show a quite incomplete website structure.

In July 2022, Doc Juicer likely shifted to another TLD, and at that point, there were already around 8k of templates available—almost half of the templates that are listed as of September 2024.

Of course, it is possible that there were more TLDs used that we were not able to trace (yet), or that in 2015, Doc Juicer simply started out with a different name.

The farm’s website under the current TLD was launched in April 2024, i.e. less than 6 months ago.

Figure 2: A comparison of web archive timelines for 3 of Doc Juicer’s domains,

with the next always replacing the preceding one which is kept as a redirect URL

The website retains the exact same layout and look as under the previous TLD, indicating it was essentially mirrored to a different TLD, possibly in order to:

-

evade regulatory actions like site takedowns,

-

bypass blacklistings by internet service providers, search engines or cybersecurity firms,

-

confuse law enforcement, or

-

manipulate search rankings to maintain visibility and attract more visitors.

These farms might just be unkillable

Tellingly, the domain registration data for both domains have been both redacted and changed over time as well.

While the first domain details are hidden via a professional “WHOIS protection” agency from Malaysia, the second domain was registered via a German domain registration service, and finally, the current domain was registered via a Russian domain registrar.

More intriguingly, while there was no identification of the domain registrant with either the first or the second domain TLDs, the third domain registration record states the registrant was a “private person” based in Yerevan, Armenia.

To make things even more complex, the current website is supposedly hosted on a server located in Canada, while specifying a city in the Middle East as its HQ address.

So just for one template farm, we already have 6 different relevant locations on 3 different continents, a host of at least 3 (but likely more) TLDs, and no real identification of an existing person or registered legal entity.

This illustrates how difficult it is to track and trace template farm operations and the entities behind them, as they leverage the global web infrastructure that allows anybody to create a website in one part of the world, manage it from another, all while probably hiding their true location behind VPN.

As should be clear by now, trying to shut down template farms is like playing a game of whac-a-mole.

You might whack one, but you can put good money down that it will either come back in a slightly different shape or form, or that other mirrored or replicated sites will pop up in its stead.

Especially if Doc Juicer is a part of a seasoned, highly organized criminal group, such an entity clearly leverages the redundancy of template farms.

Similarly to an aircraft running multiple computer systems in parallel to cope with breakdowns, skilled template farmers have multiple backup sites ready at a moment’s notice to replace the one that has been compromised in any way.

Here then, the job assigned to law enforcement with respect to template farms is thankless, as trying to shut down farms one by one simply will not work.

Even shutting down one farm in itself is likely already difficult enough given the cross-border history of farms like Doc Juicer, trying to “get em’ all” would then likely demand a large-scale, significant international law enforcement operation.

So, it’s not a stretch to state that once a template farm is run by professionals, it is essentially unkillable.

Web traffic – fluctuation, referrals, and black hat SEO

Doc Juicer’s site currently gets about 7,000 unique visitors a month, visitors stay around for about 5 minutes and visit about 5 different pages.

But traffic fluctuates wildly on a monthly basis.

How much does the web traffic of Doc Juicer fluctuate?

Web traffic data suggests that during the last 6 months, the traffic spiked significantly in July when the farm totaled around 85k visits. Similarly, April—the same month its latest TLD was set up—totaled about 58k visits.

Figure 3: A comparison of Doc Juicer’s web traffic across different channel types

in the last 5 months, with direct traffic significantly in the lead

So what could be driving these spikes in traffic?

One could assume that international conflicts, immigration waves, or even just a marketing promotion that could be open to abuse could be some of the driving factors as they might motivate people to search for fake IDs or other documents.

Alternatively, the spikes in traffic could relate to the aspect of lead generation and cross-referencing between different (but interconnected) farms.

As we mentioned previously, active site management and SEO optimization is a thing for template farmers, and the spikes in Doc Juicer’s traffic could indicate a successful digital marketing action that brought in significantly more visitors.

For example, the site could move up the search engine rankings for specific relevant queries, or the ad spend was increased considerably to attract visitors to the farm’s new TLD.

How do customers find Doc Juicer?

Looking at the website traffic journey data of Doc Juicer, it is clear that most visitors go to the site directly, i.e. they literally type the name of the template farm.

However, such a high percentage of direct traffic implies high levels of brand awareness and exposure throughout the web.

And sure enough, available data suggests there are 200k+ backlinks spread over almost 400 domains.

Figure 4: Tracking all backlink presence of a template farm gets messy quickly, as available data on Doc Juicer list more than 200k backlinks and 350+ referring domains, with the network graph above visualizing only a fraction of the data

This either means that:

-

Doc Juicer has a faithful audience that advertises the farm wherever possible, or, and more likely,

-

the farmers themselves disperse tens to hundreds of thousands of links to the farm throughout the web.

A number of the identified referring domains also share the same IP address. This could imply:

-

The existence of a network of fake or manipulated websites created specifically to boost the farm’s visibility, a common black hat SEO tactic,

-

The existence of so-called link farms, where a group of websites is set up to exchange or generate backlinks to artificially inflate search engine rankings,

-

The referring domains are part of an affiliate marketing network or a collection of partner sites that funnel traffic to Doc Juicer’s website in exchange for a commission or a share of the profits.

Figure 5: A graph showing 300+ referring domains where links to Doc Juicer are distributed, with over 200k backlinks in total. Certain relevant domain clusters even share the same IP address

What are the main web traffic destinations?

Looking at web traffic destinations, there is an interesting trend change for Doc Juicer to take note of.

While in June, most of the outgoing traffic was directed to a Telegram channel, presumably for the purposes of template ordering or payment, most of the traffic in August is directed to other template farm websites.

Figure 6: Diagrams showing Doc Juicer’s main website traffic sources and destinations

in June and August of this year, showing how even these can fluctuate widely

Once again, this points to a potentially high level of interconnectedness of some of these farms, which ultimately might be operated by the same (or at least strongly associated) group.

Where do the visitors come from?

Inspecting the available data on audience geography, most of Doc Juicer’s visitors are located in:

-

the United States (31.86% of unique visitors),

-

Kenya (27.16%),

-

India (15.05%),

-

and Mexico (5.66%).

Once again, the prevalence of US-related templates (see Figure 7 below) and the percentage of unique visitors based in the US indicates a high volume of first-party fraudsters visiting the website, while the other three countries being represented could point to a more sophisticated or organized template-purchasing activity.

What about payment methods?

Considering payment methods, PayPal is visibly an important payment method for Doc Juicer, but the website itself lists numerous other payment options like:

-

Visa,

-

Mastercard,

-

Neteller,

-

Qiwi,

-

WebMoney,

-

ApplePay,

-

GooglePay,

-

Revolut,

-

Wise,

-

Perfect Money.

Several cryptocurrencies are also listed – Bitcoin, Ether, USD Coin, Tether, Litecoin, Dogecoin, Ripple, and several others.

As Telegram is one of the main destination for Doc Juicer’s audience, it is also likely that many customers decide to process the order through the messaging app itself, most likely for the advantages of encryption, anonymity, or escrow integration mentioned above.

It needs to be noted here that we have not verified all of these payment options, as some might just be listed to create a sense of legitimacy while only a select few are actually being used.

Especially with respect to more traditional payment platforms that require proper KYC identification, it remains a question what kind of entities template farms utilize to send or receive payments.

Do they employ money mules, or create shell companies? Or both? Or something else?

An old saying in investigative journalism states that you need to “follow the money” to get to the real and most important findings.

Knowing which platforms farmers operate on and how they use them is then a critical component in uncovering inner operations of any farm, Doc Juicer included.

Doc Juicer’s catalog – you name it, we have it

Let’s go back to what first caught our eye regarding Doc Juicer – the template catalog itself.

At the time of our data gathering stage, we archived 16k+ templates across 50+ categories.

And the important thing to mention here is that the catalog is actively updated and actually grew significantly just in the past few weeks.

Currently, Doc Juicer already lists 18k+ templates, a considerable increase in a relatively short timespan.

Category-wise, the most relevant and highly represented template categories include (by order of template volume):

-

Bank statements – 2.5K+

-

Payment cards – 1.5K+

-

Utility bills – 1K+

-

Bank references – 700+

-

Invoices – 700+

-

Drivers licenses – 600+

-

Powers of attorney – 500+

-

Birth certificates – 500+

-

Marriage certificates – 500+

-

ID cards – 400+

-

Booking confirmations – 300+

-

Pay stubs – 200+

-

Visas – 300+

One can also find less frequently identified template categories like vehicle registrations, pension statements or company registration certificates.

However, these are not as highly represented, or likely demanded by customers. A fairly obscure but somehow highly represented category is “death certificates”, but more on that elsewhere.

Generic templates – alibi or marketing fodder?

One key trait of Doc Juicer’s template catalog is its comprehensiveness that doesn’t end with document templates you would expect to see used for document fraud.

A significant portion of the catalog consists of documents that could be labeled as generic, i.e. banners, resumes, birthday cards, non-compete agreements, commercial leases etc.

While in some cases, some of these templates could technically be used for fraud, they are of lesser relevance as they are not connected to an existing document issuer whose original documentation they aim to imitate.

We assume that the high number of these generic templates might be intended to either:

-

Give credence to Doc Juicer’s pretense of being just a “good ol’ regular template shop” with a legal business,

-

Serve as marketing fodder that attracts more people to the site by serving more use cases.

Document issuers – your company doc just might be in here

Unsurprisingly, the size of the catalog and number of represented doc types or categories directly implicates a large group of document issuers whose documents have been templatized.

Our data shows that more than 1000+ of document issuers are effectively targeted by Doc Juicer. Once again, these range from small, city-specific or region-specific companies to large, global corporations.

Here, we need to reiterate the message here that virtually no entity issuing official documentation falling within some of these document types can consider itself to be out of scope of template farmers.

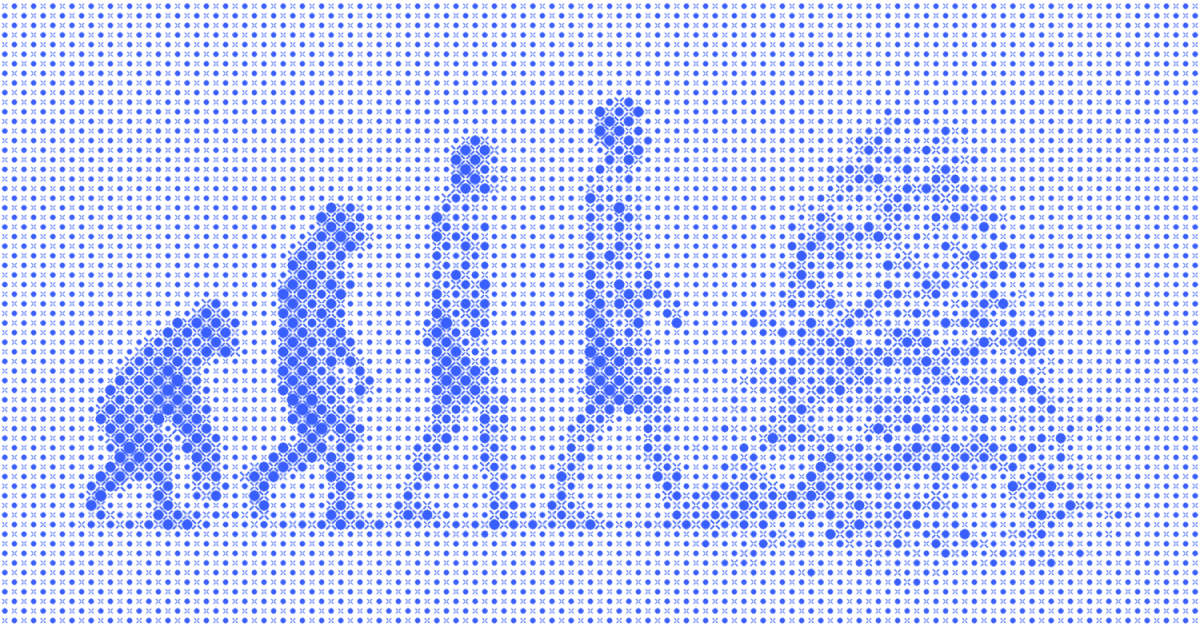

Geographical coverage and unknown docs

Doc Juicer’s catalog lists templates referring to more than 190 countries, effectively covering the entire world.

Once again, the United States dominates with respect to the volume of available templates, but there’s at least 20 different templates available for virtually any country.

Figure 7: Doc Juicer has a truly global coverage, offering

at least 20 different templates for almost every country

Most of these templates refer to nationally issued documents like IDs, passports or birth certificates, or other popular and highly represented document types like bank statements, utility bills, paystubs or booking references.

The peril of uncommon documents

The high geographical coverage raises an intriguing question: How do you perform document verification on documents tied to the smallest or lesser known countries you may have never seen before?

There’s huge diversity and variation in bank statements, utility bills, birth certificates, drivers licenses, etc, and many institutions or companies can’t reasonably be expected to have any decent idea of, for example, how a birth certificate from Vanuatu or a bank statement from a Ghanaian bank should look like.

These documents pose a unique threat since they exploit that blind spot in the document review process.

If the lack of familiarity means direct document verification isn’t possible, the fall back of contacting local authorities on the other side of the world can grind application processes to a halt., Especially if the potential volume of such documents being submitted rapidly increases once fraudsters have confirmed their success rate.

Hell, some of the documents may not even be from real institutions at all.

Our research is showing that at least a portion of Doc Juicer’s templates might not even begin with an original, authentic document template, considering cases such as birth certificates, travel visas or residence permits.

Sure, the farmers do plant the coat of arms, the national flag or other seemingly convincing graphic elements to make the product seem genuine, but a lot of these templates from different countries share a suspicious resemblance to each other with respect to document layout and other characteristics.

Realistically speaking, asking risk or fincrime professionals to have a photographic memory of every possible document out there is impossible, and a waste of their experience and creativity—which is exactly why they should be given support from modern document forensics tools like ours.

Pricing – cheap, all-in-one, or simply free

Doc Juicer applies an interesting strategy when it comes to pricing, as the price range goes from zero all the way up to tens of thousands of dollars.

There’s nothing like free

Most of the listed templates actually are offered for free. And not just generic, non-document-fraud-related templates we mentioned earlier, but also some utility bills, bank statements or, interestingly, hundreds of animal/pet passports.

Free templates from these highly-relevant categories are not of lesser quality, nor are they provided in limited formats. But with less than 100 such templates identified, they are scarce compared to the overall size of the catalog.

Still, they could have a significant role in customer acquisition, as farmers could advertise on their communication platforms through offering “free samples”, not unlike many regular businesses.

After free, cheap is the next best thing

Most often, templates cost between $16–$30.

While booking confirmations, receipts or payment card templates are on the cheaper side of the spectrum, bank statements, IDs, drivers licenses, passports or visas are on the other, costing north of $40.

No template costs more than $60, with visas being the most expensive template category on average.

Figure 8: A scatterplot showing the count (volume) and

average price of different categories of templates

But hey, if you intend to commit fraud, even that’s still an unfortunately low barrier to entry.

How about a package deal?

With respect to pricing, the most expensive items in the catalog are actually not single templates, but template packages. These can range anywhere from under 10 templates associated with a specific country, to a 50+ bank statement package, all the way up to a 2k+ package of bank statements listed for about $30k.

These package deals are a real threat as they essentially allow anyone to either:

-

obtain a huge amount of templates to launch thousands of fraud attacks, or

-

start their own template-selling operation, perpetrating the whac-a-mole problem

One thing we’re unsure of is why Doc Juicer would allow for the emergence of competition this way? As with their offers to buy document scans from customers, maybe they want to establish two-way relationships rather than just have a one-off sale.

Key insights and lessons

While Doc Juicer is the largest farm on record so far, it should not by any means be considered some sort of a template farm unicorn.

On the contrary, there are a number of slightly smaller but very similar template farms in our scope already, and there is likely to be a lot more.

Considering that and the main points raised throughout the article, there are several key lessons to take from the case of Doc Juicer:

-

SIZE MATTERS

Serial fraud takes advantage of a high number of available high-quality templates. The size of Doc Juicer’s catalog indicates that even if a smaller percentage of available templates is of sufficient quality, this will still be more than enough for scaled and en masse fraud attempts. -

THESE FARMS ARE UNKILLABLE

The farms can move from one web hosting to another quickly and repeatedly, and can place different pieces of the template farm puzzle all across the globe, making the potential for a takedown of a specific farm much harder. -

THEY HAVE A GROWTH MODEL

A farm actively asking for document scans from its audience and continuously expanding its catalog indicates that template farmers continue to proactively increase the magnitude of this threat. -

WATCH OUT FOR BLIND SPOTS

Very wide geographical coverage and document type coverage further underscores the need to rely on Ai-driven fraud prevention technology, as humans can’t be expected to efficiently and correctly account for this much document variety. As we already know from our audience, unknown documents are cited as the no. 1 concern with respect to document fraud. -

LOW-COST, HIGH-RISK

Templates are cheap and the barrier to entry for first-party fraudsters is very low. What’s worse, the potential of package-like offerings of templates can further fuel the creation of yet more fraud enablers.

All of these lessons factor in how the template farm landscape looks and dynamically evolves, and these insights should help make the necessity for advanced tools for effective document fraud detection processes abundantly clear.

Farms like Doc Juicer are here to stay, and the main thing we can do (and are already doing) is make sure its products will not penetrate the multi-layered defenses we provide.

Want to learn more about template farms and serial fraud?

Watch the replay of our latest webinar.